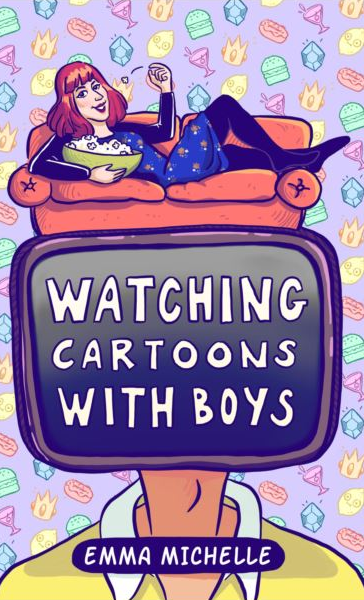

Review by Alex Creece // Emma Michelle’s Watching Cartoons with Boys wastes few words in getting to the heart of the narrative. Each chapter emphasises a different cartoon, a different memory, and a different tone.

Review by Alex Creece

I scrawled a word in my notebook as I barely finished the first page of Watching Cartoons with Boys. The word was ‘poignant’, and it kept coming back to me throughout my reading.

There is something uniquely satisfying about reading the work of local authors, particularly in creative nonfiction. There are delicious little nuggets of commonality in our Australian childhoods and a shared affinity for cartoons, and the experience of reading new literature by a young, female Australian author felt like I was connecting with a peer.

Watching Cartoons with Boys wastes few words in getting to the heart of the narrative. Each chapter emphasises a different cartoon, a different memory, and a different tone. These fluctuations parallel the tenuous nature of young romance. For instance, Chapter Three (The Venture Bros.) explores idealistic adolescent domesticity and trying on the masks of adulthood, whereas Chapter Nine (Howl’s Moving Castle) depicts bitter loss and disillusionment. As a queer woman, I was initially worried I would not be able to connect easily with the subject matter of male-female intimate relationships, however this did not prove to be an issue, as Michelle’s thoughtful construction of context and reflection made it easy to personally connect with the narrative.

Not only does Michelle explore the formative connections between our cartoon preferences and significant relationships, she also includes a refreshing amount of critique. She discusses the role of femininity to both Leela from Futurama and Linda from Bob’s Burgers, and how these representations reflect some of the confusion and double standards of being a woman. She also questions our occasionally paradoxical relationship with cartoons – our ease of ability to find humour and endearing similarities in the characters, but our cognitive dissonance and lack of self-awareness in the more problematic representations. She draws attention to the short-sightedness of youth, asking in an early chapter, ‘How can someone like [Futurama], laugh along at the self-aware satire, but take their own persona so seriously?’ (p.23) – a sentiment which is echoed in later chapters and the developmental experience of coming-of-age.

The varying forms and moods of the chapters further illustrate the sense of transition and progress inherent to the narrative. For instance, in Chapter Two (Futurama), Michelle’s playful depiction of an MSN Messenger chat is a nostalgic throwback to high school relationships. Later in the collection, she tackles narrative in script form—essentially an adultified version of a chat log—to cleverly highlight the evolving nature of youth relationships. The outgrowing of people, jokes, and priorities is captured in a manner that is relatable and unapologetic.

Chapter Five (The Adventures of Tintin) is more analytical than the other narrative-driven chapters, but Michelle is deft in her critique, and addresses the wider socio-political issues of this cartoon while still acknowledging its personal significance to her childhood. She discusses the troubled history of Tintin in representing marginalised groups, and stresses the importance of being able to appreciate the wholesome aspects of classic media without glorifying or excusing its past wrongs. This chapter feels like a stepping stone in the process of growing up – in realising that not everything is fun and games, and in developing critical thinking skills on subjects that once felt like simple entertainment.

Watching Cartoons with Boys reminds me of adolescence – the relief in what I have left behind, the pride in what I have overcome, and the nostalgia of that which has stuck with me along the way. It is—in a word—poignant.

Watching Cartoons with Boys is available for purchase online at Lulu, or in selected bookstores.