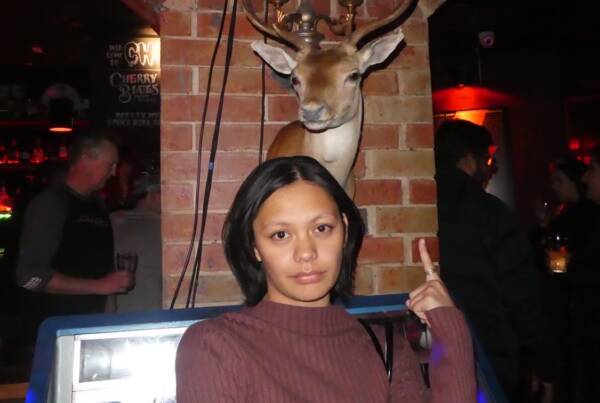

Writing by Anju Dhanushkodi // illustration by Nea Valdivia

‘Yes.’

‘Do you speak Hindi?’

(Inward groan)

I’ve only just come to realise how much this question upsets me. India is not just Hindi. There are many other languages, including my own, Tamil.

My relationship with Tamil has been a complicated journey. When I was four, we moved from India to Germany and although I’m unable to remember most of my time there, I remember learning English for the first time. I never expected I would be better at my second language than my own mother tongue, but that became apparent quickly.

I lived in Germany for one year before returning to India and then, within a few months, we moved to the UK where I became fluent in English.

I remember writing a mother’s day card at school in the UK, and instead of ‘Dear Mum’ as the teacher had written on the board, I wrote ‘Dear Amma,’ only for the girl next to me to put her hand up and say ‘She’s doing the wrong thing!’

This set in motion my journey of trying to fit in by dismissing my language and culture. I feel it’s almost a brown-immigrant rite of passage to nearly forget your first language in order to white-wash yourself, and that’s exactly what I did. By the time I was seven, I was in danger of forgetting how to speak Tamil. My Amma and Appa, desperate for me to remember my language, then enforced an ‘only-Tamil-at-home’ rule.

We returned to India when I was seven, and I studied there for a few months. I didn’t forget English, but my Tamil drastically improved, and I began to learn Hindi as well. A day after my eighth birthday, we moved to Melbourne. I was the only Indian girl in my class. I kept saying ‘no?’ after every sentence (a very Indian thing) and was determined to lose the accent.

I remember the mortifying head-nod incident, where the teacher publicly called me out in front of the whole class and taught me how to nod my head properly, as I did what’s colloquially referred to as the ‘Indian-side-bobble.’

I had friends, but I was lonely. No one empathised with me when I said I had to study after school (‘Why are you studying? We have no homework’) or knew what I was eating when I bought dosas and upma.

Once again, we moved, but this time to Sydney. My relationship with Tamil was slowly improving. This was because the suburb that I moved to had lots of Indians, and I didn’t feel the need to ‘fit in’ as much. And then, I became fast friends with another new girl who joined the school a few weeks after me. She also spoke Tamil, and suddenly, I had my first Tamil friend.

From then on, we were inseparable, and for that, I can only thank Tamil. I didn’t need to explain the food I had in my lunchbox, we sang the same Anirudh songs, and we both made dubsmashes (a predecessor to TikTok) to Tamil movie dialogues. Whereas once, I might have been ashamed, embarrassed even, I was talking to her in a language only we both understood, and we utilised this, calling the boys in our class idiots to their faces (in Tamil), and giggling and running off.

Towards the end of primary school, my parents said they were going to put me in Tamil School. I was aghast. I could speak Tamil fluently, whether it be quoting Vadivelu dialogues, or talking to my Thatha and Aachi, and I was insulted. They explained my one Tamil shortcoming – I couldn’t read or write. Reluctantly, I went. I hated every Saturday afternoon for how humbling Tamil school was. I was the best speaker in my class yet I couldn’t spell or read. Tamil is different to English in this way, you don’t write it the way you would speak it.

Whenever Tamil school had its functions, my parents would always drag me along. Although I found it a waste of time initially, I truly grew to like them. My parents grew up in a place that taught them their culture. They knew what to do when Pongal came, or the right rituals involved when it was Tamil New Year. I only had my movies, which only taught me Tamil swear words (still as valuable, I believe) This wasn’t like every other Indian function – this was specifically Tamil-based. There would be people who sang the same songs I listened to. Little boys danced to the latest kuthu beat and girls would recite Thirrukurals. With no family here, this was the closest we would get to home.

We did make regular trips to India. This was something we would save up for the entire year and eagerly await. For one glorious month, we would be surrounded by people that looked like us, spoke like us, and were our family. The India trip we took post Anju-joining-Tamil-School finally revealed the hidden motives of why my parents made me sacrifice my Saturday afternoons. I was now able to read signs on the road. I found it easier to understand cultural references and I watched on as my American cousins struggled to communicate with our childhood friends who only spoke Tamil. With a flash of pride, I would nominate myself as the translator. I suppose watching them struggle to communicate with my grandparents made me understand what a valuable asset knowing your own language is. That completely changed my mindset – I would often think of Tamil as my ‘other’ language, the answer to put down in all those surveys when the question of ‘Do you speak another language at home?’ came up.

But this? This was empowering. This let me have independent conversations with my grandparents. This let me get around the streets if I were lost. And, most importantly, it made me feel like I belonged.

Looking back, I’m almost embarrassed that I was ashamed of speaking Tamil. But I realise that embarrassment is not my fault. If there were more Tamil representation, I would have had something to identify with, something I could point to and say ‘that’s like me.’ Instead, I felt like I stuck out, and had to do my best to ‘fit in.’

I’m sick of ‘any representation is good representation.’ There’s a difference between having one movie with a brown character – who more times than not – ends up being North Indian and Hindi-speaking, and having someone like me, who eats idlis for dinner, watches Dhanush movies and speaks Tamil at home and says ‘Aiyayo’ instead of ‘Oh no!’

The biggest change in my time here in Australia has been my embracing Tamil. Whereas once, I would have let it slide if someone asked me

‘Do you speak Hindi?’ I call it out for what it is.

‘No, I speak Tamil. The oldest living language in the world.’