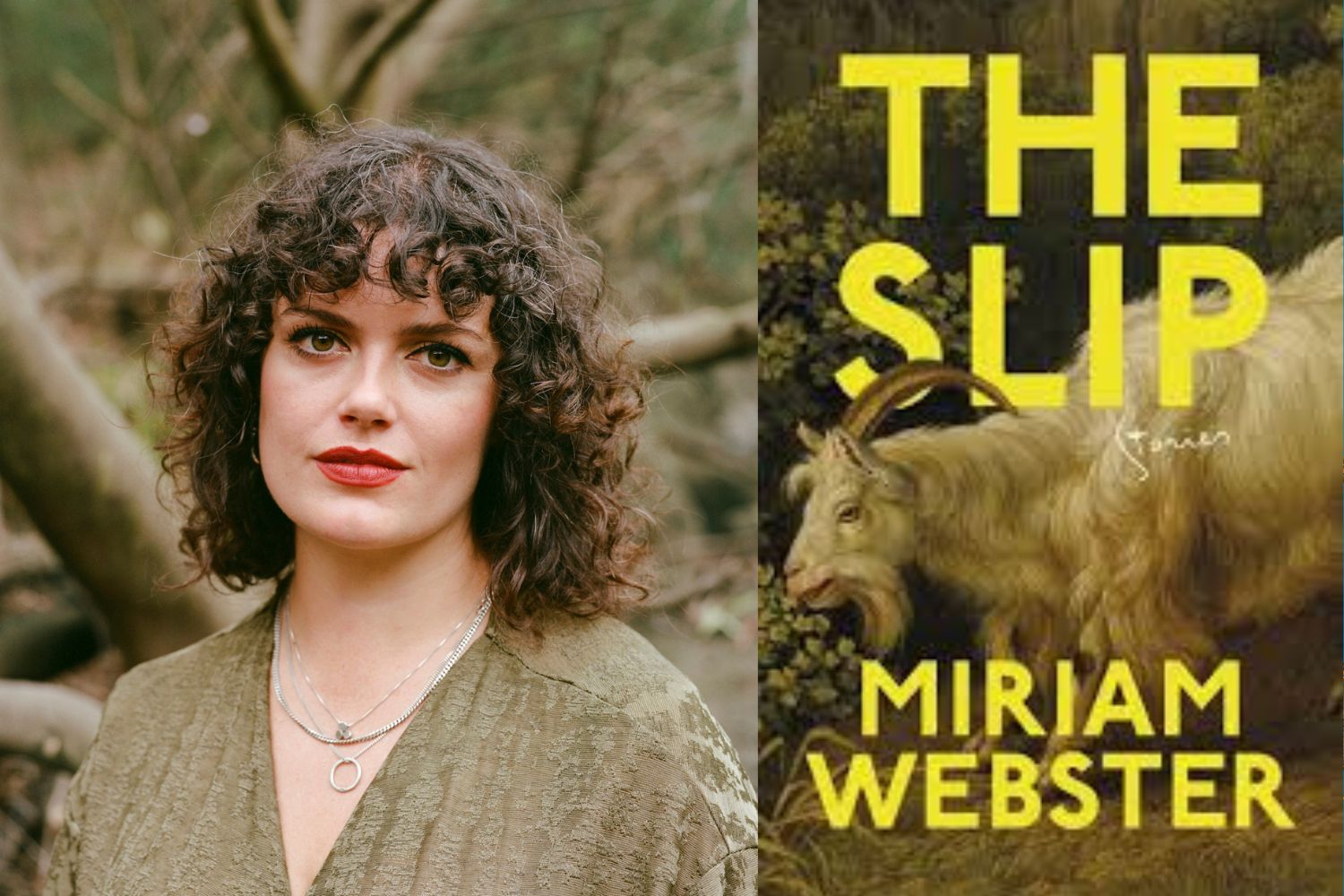

Words by Miriam Webster // photograph by Todd Cravens

One morning in the spring of 2022 my mother and I got up early, caught a shuttle from our hotel to the harbour in Surfers Paradise and boarded a charter boat we hoped would bring us close to one or many humpback whales. It was a last-ditch attempt to salvage a disastrous trip – everything that could possibly go wrong had already done so – but as we gathered with the other people on the pier a sense of optimism crackled through the party.

One morning in the spring of 2022 my mother and I got up early, caught a shuttle from our hotel to the harbour in Surfers Paradise and boarded a charter boat we hoped would bring us close to one or many humpback whales. It was a last-ditch attempt to salvage a disastrous trip – everything that could possibly go wrong had already done so – but as we gathered with the other people on the pier a sense of optimism crackled through the party.

It was a fine morning: after days of bleak, grey rain a wind had come and swept the weather out to sea. The sky was blue, with white clouds bearing down, and seabirds skimmed and coasted in the fresh, cool air. We were trying to be calm and optimistic but in fact were very stressed because my stepdad Phil, who was suffering from lung cancer, had been admitted to hospital the night before and we were scared that he might actually die before we got back from the Gold Coast. In the strange logic of that period, we never thought to change our flights. Instead we dropped $500 on a two-hour whale watching tour hoping that the whales would suddenly make everything alright.

Other tour companies had no-whale no-pay policies, but not this one. If we didn’t see a whale we would have to wear it. We didn’t give a damn. We were women on the edge and there was nothing else to lose. We did not feel certain luck was on our side. On the contrary. We were tempting fate. If we don’t see a whale, we seemed telepathically to agree, it means that he will die. In our reckless mood we declined when someone offered us some ginger tablets, even though the wind had gotten up and now the waves were tugging at the moorings, throwing the boat against the pylons. ‘Are you sure?’ they asked me. ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I’m sure’. Our ancestors were from the southwest coast of Ireland, and I believed that we would not get sick because the swell and salt was in our blood.

In other words, I was already telling stories.

This has been a problem and a talent of mine since I was little. I am often accused of over-exaggerating, and even my closest friends occasionally tire of my wild embellishments. Never let the truth get in the way of a good story, right? When people get annoyed with me I tell them I am less interested in facts than the emotional truth of things, and in this way I suppose I’ve always been a writer.

There is this interview I’ve read with Irish novelist Edna O’Brien: ‘When I say I have written from the beginning,’ she says, ‘I mean that all real writers write from the beginning, that the vocation, the obsession, is already there, and that the obsession derives from an intensity of feeling which normal life cannot accommodate’. I feel this deeply – the intensity, the desire to write. The more I write, the more I am convinced that fiction is a form of life. The best stories are encounters between selves and worlds in all their majesty and strangeness.

The boat left the dock and headed for the open sea. Mum and I stood at the prow, undeterred by spray and cresting waves. Around us, people slowly succumbed to seasickness, peeling off into the cabin. We planted our feet and swayed with the moving ocean. I had been right. We did not get sick.

The hour whiled away. I looked around and willed a whale to appear. A woman next to me was doubled over, moaning. Well into the second hour, no whales had surfaced. It began to seem impossible that we should see one and I stopped making eye contact with my mum, fearing that acknowledging this would make it true. Despair descended like a mist. We leaned over the prow, feeling spray on our faces, and joked that we were cursed.

Just then, spume on the starboard side.

Whales are undeniably magical; you can’t help feeling buoyed by the experience. I was struck with a profound sense of beauty, and also one of loss. I thought of my dad who had died the year before, of my stepdad who was dying then, of climate change and species loss and all the losses we are yet to face in this era of extinction. It made me want to finish my book, to renew my dedication to writing even if the words I had at my disposal would never quite be adequate to expressing all this grief. It made me think that it’s important to write in a way that reckons with this world, in this time, where everything is always disappearing.

On the plane home, I started a new story about a woman who goes with her family on a whale watching tour. Due to bad weather, the tour turns back part-way through and they never get to see a whale. As I wrote, the story became less about expectations and anxiety and more about the slippery, shifting line between fiction and reality. We returned home, and within 24 hours Phil was back home too. He died the next year, on the first day of winter. I kept writing, doing the grief work my book enabled me to do. The whale watching story is one of my favourite ones in my collection, The Slip, which is out today.

Maybe, to celebrate, I will treat myself to another whale watching tour. I will sway with the ocean and scan the horizon; I will feel my ancestors and my dad and stepdad swaying round me. And whether or not I see a whale, I hope that I’ll be grateful to have written my sad, weird, funny work of mourning – which is at last an affirmation of this big, wild life.