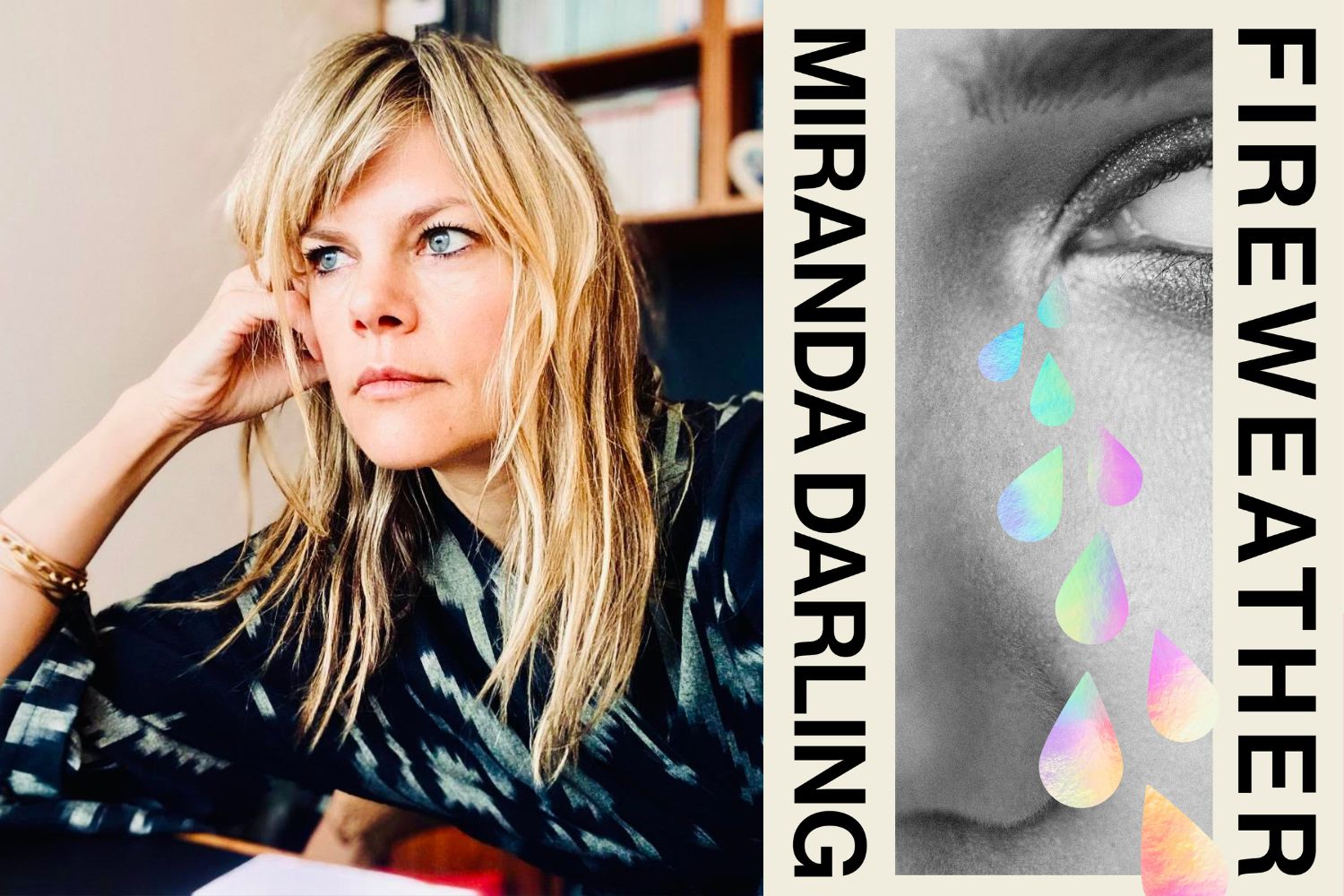

Interview of Miranda Darling by Freya Bennett

Miranda Darling’s Fireweather is a novel alive with ash, birdsong, fury, and unexpected laughter. Following on from her acclaimed Thunderhead, this second book plunges us into Winona Dalloway’s fractured yet clear-eyed world as fires rage, institutions falter, and sanity itself is up for debate. I spoke with Darling about writing into crisis, the porousness between people and nature, and why humour belongs even in the darkest flames. Hi Miranda, how are you? Where do we find you today, and what kind of weather is in your head?

Hi Miranda, how are you? Where do we find you today, and what kind of weather is in your head?

Hello Freya! I feel like this is the only question we should all be asking each other when we meet, this, and perhaps Bruce the wolfhound’s question to Winona: ‘How is the state of your heart in this breath?’ My neighbours’ cycle of demolition and construction has driven me to the library today; my weather is overcast with a likelihood of electrical storms and possible flash flooding…

Fireweather is such a visceral and haunting read, ash falling from the sky and a woman unravelling (or maybe finally seeing clearly). What first sparked this story for you?

Thank you. The fires that ravaged our country in 2019-2020 left a deep impression — these terrifying, apocalyptic scenes — and with them the greater, ongoing sense that we are not in right relationship: with the earth, with the plants, with the animals, with the ocean, and with one another. . . I wondered about other ways of being in the world and what would happen if we refused to participate in broken systems, tried to embrace the perspectives on the more-than -human world; if we reconnected to our core values and lived in alignment with them. . . It might destabilise power structures, and of course those structures would resist! What would that look like on an interpersonal level? How could a single, unremarkable human start a revolution?

Thunderhead was intimate and interior. In Fireweather, Winona is still grappling with herself, but the outside world is louder and more chaotic. What was it like writing her into this broader landscape of crisis?

It felt like the right weather to match her emotional turmoil and anguish. Winona is in dialogue with her inner voices but also with the natural world. She channels its distress but is also moved to moments of glory and wonder and humour, something which is very much part of the polarities of her character. It was a way to show how the quality of our attention matters — what we pay attention to, how we value the things we perceive matters. Attention can be a moral act; it can also be an act of resistance.

Nature becomes a kind of co-protagonist in Fireweather, sometimes comforting, sometimes ominous. What does nature mean to Winona, and what does it mean to you?

Winona is part of nature — we are all part of nature — and she experiences vividly the porousness of the boundaries between herself and other elements of the natural world. In fact, she actively seeks it in her telepathic efforts, in the compassionate delicacy of her attention, her sometimes paralysing sensitivity to it. . . I seek that reciprocity too. For me, nature is a source of awe, and immersing myself in the natural world is the way I recalibrate; it keeps me alive to the beautiful mysteries of the cosmos. I take a lot of photos of clouds — phenomenons of light! — and of trees. I think maybe it’s a way of paying rapt attention to something so much greater than myself, of honouring it, and of bathing my eyes in beauty.

Winona’s grip on reality seems slippery and yet so much of what’s dismissed as “madness” in her feels like a rational response to a world on fire. Were you trying to challenge how we define sanity?

Yes. Winona is refusing to capitulate — in her quiet, anxious way — to the demands of a world out of balance and off kilter. Nothing that truly matters is valued in this system and, although her response is eccentric perhaps, it is at least a recognition that ‘nothing is as it should be’ and she won’t pretend otherwise. She refuses to give in, to allow herself to be controlled, to behave as expected, and she is driven by a desire for freedom and a very pure Love. Ultimately, one might even say this is how a person should be. . .

Fireweather feels timely in a way that’s almost uncomfortable, climate collapse, maternal exhaustion, institutional mistrust. Do you consider your work political, or do these themes simply follow the characters?

If we take political to mean critical of power structures and social dynamics and market forces then yes, its deeply political. I think of Winona and FIREWEATHER as a rock thrown into the pond: I am seeking ripples, change. I believe that we each hold within us the power for significant transformation and that indeed nothing will change in the world around us until we recalibrate our own values and live aligned with them. There is power in deep disobedience, in the refusal to participate in the collective manipulation — in refusing to fear, to crave, to seek to dominate — and a great freedom too. We need imagination to rethink our extractive relationship with the earth and with living beings and also with each other. We can begin by noticing, by appreciating beauty, by doing one true or good thing every day that has no economic or power-related value. . . These choices are so small and yet they are within the possibility of each one of us: with these tiny reversals, we pave the way for greater ones. What would our world look like if our systems put Life at the centre, instead of power and profit?

You write so fearlessly about women in emotional and psychological extremes. What do you think we’re still getting wrong, culturally, about female rage, grief, or mental illness?

Without being too flippant, I would say that female rage is often interpreted as mental illness! I also think it is still the emotion we women ourselves find the hardest to express as it remains culturally unacceptable. We swallow our rage, we hold it, it is forced to come out in other ways. . . As Winona says: “It’s not safe for a woman to talk, but it’s usually safe for a woman to cry. ” Grief is perhaps more permissible, yes, but only if it can be attributed to clear, ‘acceptable’ external causes and even then it cannot be too intense nor last too long. I think our culture does not know how to hold these powerful emotions — we have forgotten or have never learned how. We have lost touch with our rituals, with the spirituality of our beings. Women as mothers and partners, daughters and sisters, are the ones who do most of the emotional holding so perhaps it is destabilizing when they in turn need someone to hold space for their agony.

There’s a dark humour threaded through even the most unhinged moments. Is that a conscious tool when writing about trauma and collapse, or does it sneak in on its own?

Oh its very conscious and also very much indicative of how Winona sees the world. Winona has a heightened sense of the absurd which gives her a measure of perspective and a sense of her own ridiculousness. This is something I think I share with her. As a writer, I use humour very deliberately. It does often bubble up on its own during scenes, but I make a conscious choice to seek it out. Humour crucially eases the intensity of the story in parts, and I see absurdities and felicitous juxtapositions everywhere. It brings perspective to the shadow-sides of the story, and once you have seen something for its absurdity, it becomes impossible to unsee. Humour can be deeply subversive used this way. I also use humour when I write about ‘difficult’ topics because many of us are well-defended, but even irony or wry laughter can punch through tough resistance.

Can you tell us anything about what you’re working on next? Will we see Winona again, or is it time to explore new voices?

You will meet Winona once more. I can’t really say more, except that there may be icebergs ahead, and that you can be sure Winona will be once again accompanied by all her voices. . .