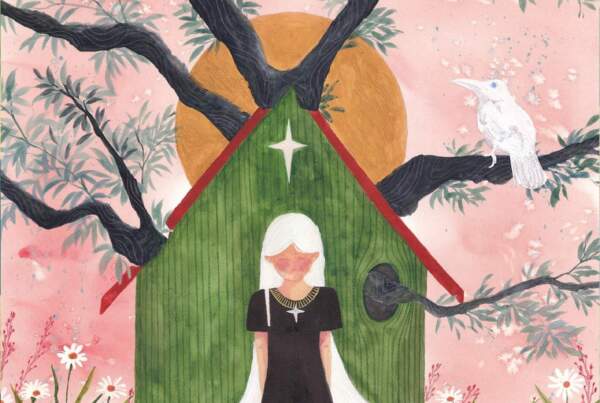

Words by Jen Bryant // illustration by Jinyue Fan

The morning after I left my then-husband for good, I arrived at work wearing a fake smile and rumpled clothes hurriedly shoved into my suitcase the night before. As I stood in the bathroom, squeezing Visine into my eyes before a big presentation, the lines of a familiar poem came back to me: it’s not the crutches we decry / it’s the need to move forward / though we haven’t the strength

*

Nestled among the thick books in my home library is a slim volume of poetry, its contents so familiar by now that I hardly need to crack the cover to summon the words inside: Nikki Giovanni’s Cotton Candy on a Rainy Day.

I first encountered Giovanni in my high school library. We had to memorize and recite two poems for public speaking class, an assignment that filled me with dread. I much preferred the comfort of my strategically chosen desk in the back of the classroom, where I doodled and daydreamed, to having twenty-three pairs of adolescent eyes on me. Still, I liked the teacher, and after skipping class one too many times in favor of furtive bathroom cigarettes with my best friend, I needed the A.

I’d already selected one poem—a dramatic, slightly overwrought breakup ballad by Pablo Neruda that spoke to my teen-goth heart—but needed a second. I pulled books off the shelf at random until I found one that looked intriguing. The cover was shades of pink with funky lowercase 1970s lettering. A Black woman’s face was sketched in profile, face tilted slightly upward, gazing towards something unseen.

The book fell open to ADULTHOOD II. I read the opening lines: There is always something / of the child / in us that wants / a strong hand to hold / through the hungry season / of growing up

According to the stamped borrowing card nestled into a cardboard flap at the back of the book, this one had been gathering dust since 1987. I decided to give it a chance.

*

Born in 1943, Nikki Giovanni came of age amid the civil rights movement and growing progressivism of 1960s America. By the time Cotton Candy on a Rainy Day was published in 1978, she was already a well-respected author in the Black Arts Movement. Her work seamlessly wove the personal and political, providing readers with a portrait of being young, Black, and female in a country whose culture was rapidly changing.

The ethos that Giovanni contributed to as an activist in the 1960s and 70s would form the core of her beliefs throughout her life. In a 1999 speech, she famously remarked: “What’s the difference between dragging a Black man behind a truck in Jasper, Texas, and beating a white boy to death in Wyoming because he’s gay?” To Giovanni, all struggles for liberation are inextricably interconnected, a theme her work has explored from the start. Like the woman on the cover of Cotton Candy on a Rainy Day, Giovanni’s gaze has always been leveled at a better and more equitable future for all people, one that hovers just out of sight. She can see it, even if nobody else does.

Despite the social urgency behind her work, Giovanni’s poems aren’t heavy-handed. Rather, they’re refreshingly straightforward, even playful at times. To Giovanni, finding community and contentment in the midst of struggle isn’t beside the point, it is the point. What’s more, happiness doesn’t have to be restricted to lofty pursuits: “joy is finding a pregnant roach / and squashing it.”

I didn’t know any of this back then, but the poems in that little pink book spoke to me just the same. Although our lives were different, Giovanni’s words extended a hand across space and time. Sure, she wasn’t a disaffected teenager slowly suffocating in a small-town high school, but she understood what it was like to give your heart to the wrong person (if you love me why / do i feel so lonely / and why am i practicing / not having you to love / i never loved you that way). She was familiar with the problems of capitalism that I was just beginning to understand (her life looks occasionally / as if it’s owed to some / machine / and the only winning point / she musters is to tear / mutilate and twist / the cards demanding information / payment / and a review of her credit worthiness). She even spoke to my inner turmoil as I nursed my first secret crush on another girl: women aren’t allowed to need / so they develop (…) female lovers whom they never touch / except in dreams

Giovanni’s poetry was among the first I read that felt modern and accessible. As I devoured her book, I learned that poetry didn’t have to be an unattainable intellectual pursuit, full of old-fashioned words and iambic pentameter; it didn’t even have to rhyme. Poetry could also be about politics, or aliens, or that dumb boy you can’t stop thinking about even though he objectively sucks. I was hooked.

*

Over the years, I’ve moved across state lines, downsized and de-cluttered, and even sold beloved books to make the rent, but Cotton Candy on a Rainy Day is still with me. Decades removed from that teenage girl in the library, I’m drawn again and again to that dog-eared paperback with the cracked spine, discovering new lines that speak to whatever moment I’m in.

Sometimes Ms. Giovanni’s words shimmer unbidden to the surface of my consciousness, often when I’m least expecting it.

In the depths of a creative dry spell, my own words drowned out by responsibilities: my poems get decimated / in the dishes the laundry / my sister is having another crisis / the bed has to be made

Navigating the gray areas of adult life, getting hurt and hurting others in return: Before we ourselves / Meet the man / Lie to the bill collectors / Don’t know where the mortgage payment is coming from / It’s difficult to understand / A weakness

As I Zoomed and doom-scrolled through a never-ending string of gray Ohio pandemic days, starved for human connection: They have asked / the psychiatrists psychologists politicians and social workers / What this decade will be known for / There is no doubt it is loneliness

*

Once, I had the chance to meet her. I lived in Virginia at the time, and she was a professor at Virginia Tech. A fellow bookworm friend called to tell me that Giovanni would be performing at a festival in a neighboring town. Did I want to go?

I did, but in the days leading up to the festival, I got cold feet. What would I say? How could I possibly convey how much her work meant to me? I wanted to meet her—of course I did—but would she want to meet me?

In the end, I got cold feet. The moment passed. I moved away; Giovanni retired. The opportunity was gone.

Perhaps meeting her in person was less important than getting to know her on the page. Giovanni’s work came into my life at a crucial time, when I was just starting to understand the world around me and my place in it. She made it seem like you didn’t need permission to write about all the messy, beautiful, mundane aspects that make up a life: varicose veins, electric bills, lonely nights. Her words showed me that writing can be a portal, offering new ways to see each other and ourselves. That honesty in writing is a sacred, vulnerable way to put yourself into the world, and that when others read your words, they might feel less alone.

*

For my public speaking class assignment, I read Giovanni’s poem WOMAN. It’s mercifully short, but that’s not why I chose it. At the time, I was enmeshed in a messy love triangle, slowly coming to terms with the fact that the guy I was falling for was never going to choose me back. The poem made me feel like my life could go on, even if I had to cut him out of it.

As I read, my classmates fiddled with their hoodie strings, glanced at the clock, or shuffled through notes for their own upcoming presentations. Most weren’t overly focused on me.

But one girl, sitting in the second row, watched me the entire time. She had a sweet smile, and she liked to adorn her perky ponytail with orange-and-blue ribbons, our school’s colors. Lately, her eyes were often red-rimmed. People said her boyfriend was kind of an asshole; when she showed up one day with her arm in a sling, whispered rumors said he’d pushed her down the cafeteria stairs. Nobody knew what to do, so nobody did anything. Her face, once trusting and open, had begun to close like a fist.

I finished reading and hurried back to my seat, relieved that the presentation was over. When the bell rang, her eyes followed me to the door.

A few days later, she stopped me in the hallway before class. “I really liked that poem you read,” she said quietly. Her eyes darted nervously, like she was afraid someone might overhear. “Who wrote it, again?”

“Nikki something?” I replied, pushing past the discarded gum wrappers and crumpled notes in my backpack until my fingers brushed the book. I squinted at the pink cover. “Uh…Giovanni.”

We stood there awkwardly for a moment. “Here, you can take it if you want,” I said, extending the cotton-candy-colored book as an offering. “Just drop it off at the library when you’re done.”

She smiled, hugging the poems to her chest. “Thank you.”