Writing by Ellen Muller // Beyond Toro’s signature use of dark fairy-tale like figures, it’s easy to assume that a love-story between a mute janitor and captive amphibian creature, is utterly distinct.

Writing by Ellen Muller

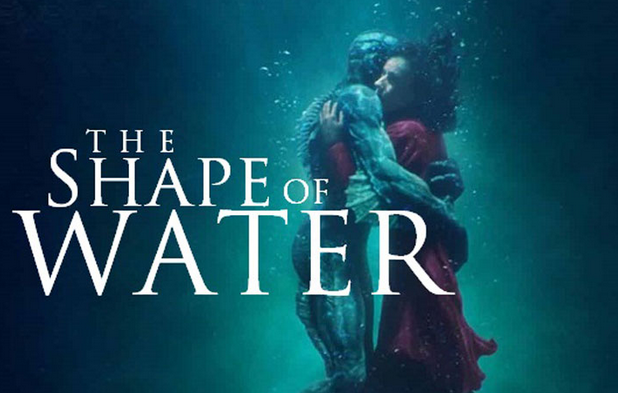

At a glance, director Guillermo del Toro’s newly released film The Shape of Water, seemingly shares little in common with his earlier film Pan’s Labyrinth (2006). Beyond Toro’s signature use of dark fairy-tale like figures, it’s easy to assume that a love-story between a mute janitor and captive amphibian creature, is utterly distinct – incomparable even, to a story which follows a ten year old Spanish girl who must complete three tasks for a faun before the moon is full. Surprisingly, despite how intensely unique these two plotlines initially appear, and despite being set in two very specific and discrete eras, The Shape of Water and Pan’s Labyrinth have strong parallels, particularly from a historical and feminist perspective.

As I watched The Shape of Water (and of course after thinking a lot about how great it would be if the creature turned out to be Old Gregg from The Mighty Boosh), I thought of Pan’s Labyrinth in comparison; there are deeper trends linking these two films which risk being overshadowed by the sheer presence of mystical creatures –Toro’s use of an ‘outsider’ female protagonist, and fantasy as a medium to reflect on humanity’s recent history.

While Elisa (The Shape of Water, Sally Hawkins) and Ofelia (Pans Labyrinth, Ivana Baquero) belong to two very distinctive stories and historical periods, both of their plots are instigated by an encounter with a mystical creature, and centre around challenging an archetype of accepted norms and toxic masculinity specific to their time (interestingly both creatures are played by an elaborately disguised Doug Jones. He would’ve made a great Scooby Doo villain). For Elisa, a need to defy her boss, Colonel Richard Strickland (Michael Shannon), is created when she discovers and falls in love with a mysterious amphibian creature held captive in the classified government facility where she works. Whereas Ofelia’s obedience to the faun’s orders means going against the standards of her new officious step-father, Captain Vidal (Sergi López).

In these films, both Toro’s central female characters mirror the classic fairy tale paradigm of the princess who is isolated for her uniqueness, and domineered by an evil oppressor. Despite their age difference, Elisa and Ofelia each struggle with comparable feelings of deep alienation from a society and political atmosphere which surrounds their existence. More obvious, they are also both directly categorized as princesses during their stories: with Ofelia driven by the belief that she is ‘Princess Moanna of the underworld’, and The Shape of Water’s beginning and concluding narration referring to Elisa as ‘the princess without a voice’.

Similarly, the villains, Strickland and Vidal, also share strong parallels despite their characteristics being much more heavily rooted in their film’s historical settings. Both men have a high position of authority serving their country’s existing power structure (Strickland as an American government agent, and Vidal as a military Captain in a ‘new’ Nationalist Spain). What’s more, they both give the impression of having earnt their status through their strict discipline, cruelty, and a fervent commitment to the traditional values both power structures represent.

The post-war and Nationalist-led Spain, in which Ofelia’s fictional story is entwined, placed a fundamental importance on a return to traditional gender roles, and heavily reinforced this through new legislation designed to restrict women. Additionally, being the first decade under the Nationalist regime, this period experienced intense oppression and mass ‘cleansings’ of political opposition. This true historical background is visible throughout Pan’s Labyrinth, but Vidal in particular truly embodies the hegemonic masculinity and militarisation that were core ideals of Franco’s dictatorship. Likewise, while The Shape of Water is scattered with examples of the film’s true historical context, Strickland arguably most personifies the particular suspicion which marked American politics during the ‘Space Race’ and Cold War in general. Moreover, he personifies the underlying prejudice and staunch resistance to change, that the rights based movements of the time (particularly the Civil Rights Movement) were challenging.

The historically fraught backgrounds of Elisa and Ofelia’s stories are unique, however the isolation these characters feel has a gender and class element in common. For Ofelia, while her age is a large component of her figurative voicelessness, wider gender-based politics are a noticeable influence in the situation she finds herself in. As a child, Spain’s stark reversion back to a patriarchal structure occurring at that point, is particularly relevant to Ofelia’s situation by how it affects her heavily pregnant mother, Carmen (Ariadna Gil). The audience never get to hear Carmen’s perspective, yet her reassurance to Ofelia, when asked why she has remarried following the death of Ofelia’s father during the war, that ‘you will understand when you’re older’, hints at Carmen’s lack of choice to remain a single parent or to refuse Vidal’s request. Furthermore, our only knowledge of Ofelia’s deceased father is that he worked as a tailor, suggesting that the family’s working class background could easily be another aspect limiting Carmen’s freedom to choose.

In comparison, Elisa’s identity – as a disabled, working class woman in 1962, surrounds her with an invisibility, evident for instance when she and her African-American co-worker, Zelda (Octavia Spencer), are automatically dismissed of being any kind of threat by Strickland. This utter indifference to their presence, allows Elisa to regularly visit – and later rescue, the amphibian creature, without arousing any suspicion. Conversely however the fact that Elisa is a woman physically incapable of speaking for herself is the root of Strickland’s attraction to her. While Elisa has the company of other individuals considered ‘different’ during this era – such as Zelda, and her closeted friend Giles (Richard Jenkins), she nevertheless carries a sense of isolation, only amended when she discovers the amphibian creature – ‘the loneliest thing I have ever seen’.

By rescuing the creature Elisa begins to embrace her own ‘otherness’, and arguably reflects the film’s larger historical setting: a time that was slowly making progress and in the beginning stages of embracing difference. Whereas in Pan’s Labyrinth, the faun and his tasks Ofelia chooses to undergo, are frequently interpreted as purely Ofelia’s imagination attempting to make sense of the harrowing circumstances which surround her.

What’s fascinating about these two films when analysed together is how Toro is able to utilise traditions within the fantasy/mythical genre to meaningfully represent moments and values of the twentieth century. Whilst Pan’s Labyrinth and The Shape of Water are seemingly exploring completely separate themes, the loneliness experienced by the two female protagonists reveals an ongoing dialogue with Toro and his audience, over recent history. Through his protagonists who face isolation from both their time and villainous authority figures, Toro is perhaps challenging the viewer to truly reflect and learn from humanity’s past and its intolerance to difference.