Writing by Meggie Royer // Photograph by Julie Young // In October 1999, Maggie Wardle, a student at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, was shot and killed by a former boyfriend, Neenef Odah, a day after he learned that she attended their school’s homecoming dance with another man.

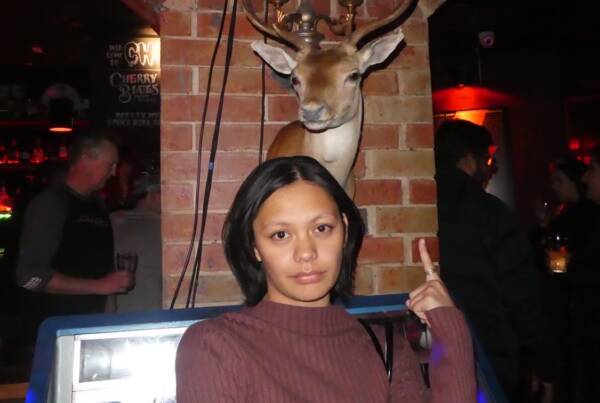

Writing by Meggie Royer // Photograph by Julie Young

I work at Women’s Advocates, the first domestic violence shelter in the U.S. When our crisis phone line opened in 1972, followed shortly by our shelter, it would take another 20 years before marital rape became a crime in all fifty states. Now, several decades later, we have made enormous progress against domestic violence in the United States. And yet – where is the #MeToo movement for victims of this crime?

In October 1999, Maggie Wardle, a student at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, was shot and killed by a former boyfriend, Neenef Odah, a day after he learned that she attended their school’s homecoming dance with another man. When I discuss Maggie’s case with students in domestic violence education sessions, I ask them if they think any physical violence existed in their relationship prior to her boyfriend murdering her. Nearly every student nods emphatically.

But there wasn’t. There was no physical abuse – it was all emotional. There was no sexual violence, no strangling, no slaps to the face or abdomen. There was, however, isolation, angry phone calls, verbal abuse, accusations of cheating and an incident in which Odah punched through a door after speaking to her.

But he never touched her. And he was her boyfriend. Not a stranger. Not a coworker. Not an acquaintance. Not a friend.

Because of this, Maggie would not be counted in the present day #MeToo movement. In 1999, she barely counted either. Most of the results that a Google search of her name shows are for other Maggie Wardles – their Instagrams, LinkedIns, and Facebook pages. According to the Internet, Maggie Wardle barely existed.

Maggie’s case is all too common but she’s yet to have a #MeToo movement. Just like all the women whose husbands raped them prior to the 1990s, when this form of violence was finally criminalized. Just like Grace Costa, who was profiled in a December 2015 New Yorker essay on strangulation after her former boyfriend strangled her with a phone cord. Grace’s memory is filled with holes. Her ears are filled with ringing. She suffers from migraines; she blacks out, she forgets things. That is what strangling does. Grace does not get a #MeToo movement. Neither does Vanessa Danielson, who was set on fire by her boyfriend in Minneapolis in the fall of 2017. Neither does the author Leigh Stein, whose 2016 Washington Post essay about the control, humiliation, and gaslighting she experienced at the hands of her now-dead former partner instantly opened a comment section dizzying in its display of accusations and blame – he never touched her, so it wasn’t abuse. He never hit her, strangled her, sexually violated her, never cut off her circulation or threw her into a wall- so it wasn’t abuse. So it does not qualify for #MeToo.

These are the myths we are fed about what constitutes abuse and what doesn’t, and these are the myths we will continue to believe, when we forget about domestic violence. When it is relegated to a private realm in our collective consciousness, when we continue to insist it only occurs within a home, where it is the abuser and the victim’s business and no one else’s.

It is our business. It is our business every time we forget, or choose to ignore, that it takes a woman seven attempts on average to leave an abusive relationship. When we forget, or choose to ignore, that most often when a man refers to his former partner as his “crazy ex-girlfriend,” it really means, “She wasn’t crazy. But I made her feel like she was.” When we forget, or choose to ignore, that screening for domestic violence is not optional. It is necessary. When we forget, or choose to ignore, that 44% of working U.S. adults say they have experienced the effects of domestic violence in the workplace.

I work at Women’s Advocates, the first domestic violence shelter in the U.S. When our crisis phone line opened in 1972, followed shortly by our shelter, it would take 20 years before marital rape became a crime in all fifty states. Now, several decades later, we have made enormous progress against domestic violence in the United States.

And yet, where is Grace Costa? Where is Vanessa Danielson? Where is Leigh Stein? Where are they in our #MeToo movement? Where is our collective outrage about domestic violence?

I remember Maggie Wardle. I remember every doctor who forgot to screen. I remember every scratch around a woman’s neck. I remember every person who forgets there was a first domestic violence shelter. I remember the 2017 film The Light of the Moon, in which Brooklyn Nine-Nine star Stephanie Beatriz plays Bonnie, a woman rebuilding her life after being raped and beaten by a complete stranger in a dark alleyway. I remember how we would consider this to be Bonnie’s #MeToo movement. Unless she was raped and beaten by a boyfriend, or a spouse, or her father, or her grandfather, or her brother. Because that would be domestic violence. And domestic violence does not compute into our #MeToo equation, despite the fact that half of all female homicide victims are killed by a current or former intimate partner.

I remember Maggie Wardle. I remember her. Do you?