Writing and art by Seth Lukas Hynes // Gender is an incidental and usually irrelevant attribute of giant monsters, but in King of the Monsters (and the Japanese franchise), Godzilla and Mothra are explicitly gendered as male and female (respectively).

Writing and art by Seth Lukas Hynes

Even monsters are susceptible to casual sexism.

Godzilla: King of the Monsters is the third American Godzilla film, the sequel to 2014’s Godzilla, and the first Hollywood appearance of famous monsters (or “kaiju”) Rodan, Mothra and Ghidorah. King of the Monsters had a huge responsibility to do these kaiju justice and honour the six-decade, twenty-nine-film legacy of the Japanese Godzilla franchise.

King of the Monsters is an immensely-entertaining monster mash with outstanding effects and battles, but I wish director Mark Dougherty had put more effort into the human narrative foundation, as the plot is sloppy, contrived and poorly-paced, save for some engaging character arcs.

I also wish Mothra hadn’t been so badly shortchanged.

Mothra, introduced in the 1961 standalone film of the same name, is one of Godzilla’s most frequent and beloved kaiju co-stars. While one of the weaker kaiju in the menagerie (a giant moth fighting a fire-breathing dinosaur goes about as well as you’d expect), she is one of the most intelligent, and is usually characterised as a benevolent protector of humanity or nature.

In design and tone, King of the Monsters nails its portrayal of Mothra, presenting her as a clever, almost angelic creature who perseveres against extreme odds and far more powerful foes, and she has some awesome moments.

But her role within the plot is limited and somewhat problematic.

Mothra is born as a larva (leading to a cool horror-action sequence), has a bonding moment with a girl named Madison (Millie Bobby Brown), cocoons herself and emerges in her adult form, then appears before the monster research organisation Monarch to inform them of Godzilla’s survival, after he was struck with a deadly weapon. Mothra ultimately joins Godzilla in Boston to fight Ghidorah, the film’s monster villain, but splits off to fight Rodan, Ghidorah’s pterosaur “henchman”. Mothra beats Rodan but is then disintegrated by Ghidorah, after which her energy revives a wounded Godzilla.

Gender is an incidental and usually irrelevant attribute of giant monsters, but in King of the Monsters (and the Japanese franchise), Godzilla and Mothra are explicitly gendered as male and female (respectively). Ghidorah is male – he is usually called “King” Ghidorah – and while Rodan’s gender rarely comes up in the franchise, he’s generally assumed to be male by fans because of his brash overconfidence, which is traditionally considered a masculine trait.

I find it disappointing that Mothra, who is such a beloved kaiju and the only clear female one in the film, serves only to reveal, help and finally die for Godzilla, and receives far less development than her fellow kaiju.

Mothra and Rodan, who are the main monster allies of Godzilla and Ghidorah (respectively), each get their own introductory action scene, but Rodan’s is much more substantial.

Right after hatching, a larval Mothra thrashes about in confusion and anger, killing several Monarch guards, before she is calmed by Madison and her mother Emma’s (Vera Farmiga) Orca sonic invention.

Rodan is awoken by the Orca, fully adult, from his slumber in a Mexican volcano. The hurricane-force wind from his flight destroys the city below, and he savagely pursues and destroys several fleeing Monarch planes before being defeated by Ghidorah.

Both Rodan and Mothra are subdued in their introductions, but Rodan is dominated by a more powerful monster, while Mothra is essentially manipulated into becoming placid by Emma’s Orca device. Rodan, as an adult monster, has far more vicious agency in his mayhem, while Mothra lashes out because she’s basically a newborn in distress. Rodan is deliberate; Mothra is agitated, unthinking and literally juvenile.

In King of the Monsters, an ostensibly male monster is given more deliberate agency in his introduction, while the female monster is practically hypnotised and almost literally infantilised in her introduction.

Going back to the climactic battle, I should mention that Mothra has died to empower another monster before: in the 2001 Japanese Godzilla movie GMK: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack.

In GMK, Godzilla is a demonic villain, and Mothra is one of three mythical guardian monsters summoned to defend Japan from him. During the climax, Mothra and Ghidorah (in his single heroic role in the entire franchise) join forces to fight Godzilla. Mothra is incinerated by Godzilla, but her essence infuses the fallen Ghidorah, reviving him and unlocking his full powers.

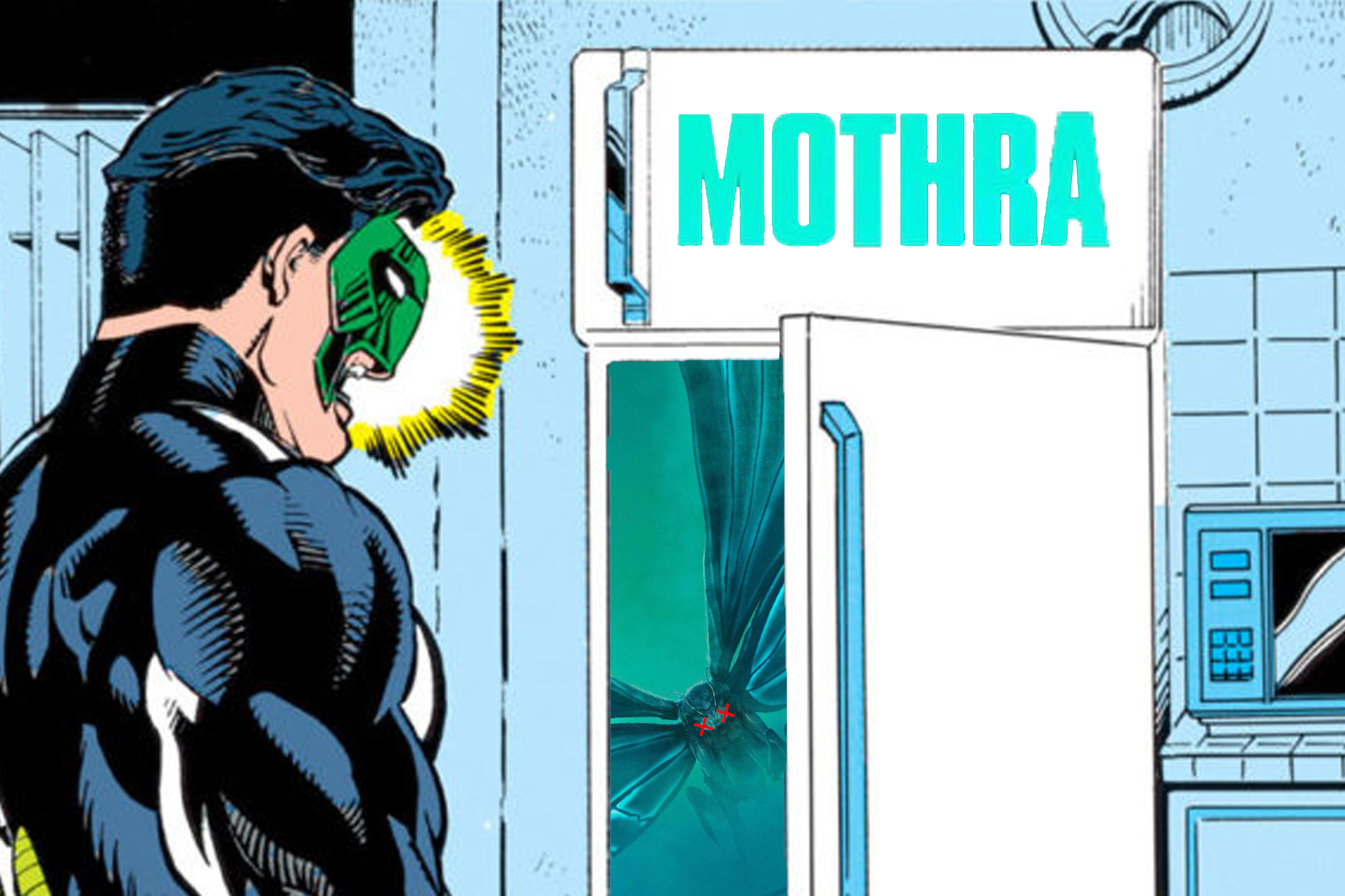

Both instances of Mothra dying to strengthen another (male) monster come across as examples of the notorious “Women in Refrigerators” trope.

Defined by American comic book writer Gail Simone in 1999, “Women in Refrigerators”, or “fridging”, refers to the alarmingly common fictional scenario of a female character being killed, raped, abused, crippled or de-powered to motivate a male character and drive forward his character arc. The name comes from an issue of the Green Lantern comic series in which hero Kyle Rayner returns home to find his girlfriend Alexandra murdered and stuffed in his fridge.

While I love the Max Payne game series, the first game has probably the worst case of fridging I’ve ever experienced.

Male characters can be fridged too: the death of cop Alex Balder, and protagonist Max being framed for his murder, is the instigating incident for Max’s one-man war against the New York mob. But in the prologue, Max’s wife Michelle and their baby are murdered by junkies. This tragedy has a loose connection to a drug-related conspiracy Max uncovers, but otherwise the murder of Max’s family has no bearing on the plot, only providing a basis for Max’s depression and atmosphere for a nightmare sequence later in the game.

‘Essentially, when we say that a female character has been “fridged,” we’re saying that she has been treated like an object who has less human worth than the men around her. She is valuable to the extent that her pain can motivate them,’ writes Constance Grady of Vox.

Mothra dying to literally empower another monster is not a classic fridging, but it’s still a female character being killed off for the growth of a male character, and thus she is treated as subservient and disposable.

But I would assert that Mothra is fridged in King of the Monsters, but not in GMK.

Mothra has a much more proactive and direct role in GMK‘s final battle against Godzilla than against Ghidorah in King of the Monsters. She initiates the fight against Godzilla, with Ghidorah arriving a while later, and she lands a couple of solid attacks against Godzilla. Godzilla is also such a powerful opponent that Mothra and Ghidorah are roughly equal (to be precise, equally weak) against Godzilla, at least until Ghidorah is energised.

In King of the Monsters, in which Ghidorah is the villain, Mothra barely gets to fight Ghidorah, instead fighting the secondary villain Rodan.

It doesn’t matter that Mothra willingly sacrificed herself in both GMK and King of the Monsters.

Ghidorah is arguably the main monster character of GMK (alongside Godzilla), but Mothra is still an active and effective member of the conflict. Crucially, Mothra has worth in the fight. Mothra’s sacrifice is therefore an act of saving a partner in a dire situation, not the cursory killing of a female character just to drive or strengthen a male character.

Godzilla is objectively a more powerful kaiju than Mothra in King of the Monsters, and certain circumstances may have rendered Mothra’s sacrifice pointless. After Godzilla is critically-injured by a new weapon, Dr Serizawa (Ken Watanabe) heals him using a nuclear warhead. During the final battle, the human characters indicate that Godzilla’s energy is rising rapidly, and he’ll soon release a nuclear explosion. Godzilla is rendered unconscious by Ghidorah, but Godzilla’s “meltdown”, which obliterates Ghidorah, likely would have happened regardless of Mothra’s intervention.

Rodan only appears in his introduction and in parts of the final battle, with Mothra receiving more screen-time, and yet Mothra is by far the least-developed kaiju in King of the Monsters. Mothra is grossly devalued throughout the narrative, and dies to support the male monster hero.

Given that she is established through a scenario that gives her little agency, has hardly any constructive role in the narrative before the final battle, barely fights the main villain and instead fights Rodan, a secondary male villain established with greater maturity and agency, and yet she still gives her life to help Godzilla, which might not even have been necessary, this story arc seems like a clear case of fridging.

The marginalisation of women in popular media, including the few prominent or leading roles for women in big franchises, the far fewer spoken lines for female characters than male characters and the limited opportunities for female filmmakers, has received much discussion in recent years.

It took over a decade for the Marvel Cinematic Universe juggernaut to deliver a female-led superhero film in February 2019’s Captain Marvel, which also happened to be the MCU’s first female-directed film (albeit co-directed; Captain Marvel was directed by Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck).

The Avengers heroes are predominantly male and often embody a smug, wisecracking asshole-with-a-heart-of-gold archetype (which is a flavour of toxic masculinity), and female supporting characters in the MCU often fill a perky, confident moral support and love interest role for the heroes.

Black Widow (Scarlett Johansson) has had a raw deal as part of the Avengers, with her excluded from Age of Ultron merchandise, being given an almost motherly role and an out-of-nowhere romantic connection with Bruce Banner (Mark Ruffalo) in Age of Ultron, and the film apparently implying that she’s a monster partly because she’s sterile. This ham-fisted suggestion renders Black Widow’s otherwise noble sacrifice in Endgame rather icky, as Grady observes, because ‘there’s also an insidious implication that Natasha’s infertility renders Black Widow just a little bit more disposable than the rest of her teammates.’

Through an unlikely, beastly avenue, King of the Monsters perpetuates this marginalisation of female characters.

It’s disconcerting and surreal that screenwriters Dougherty and Zach Shields imposed gender bias (even unconsciously) on a giant moth, but Mothra’s flimsy narrative role and fridging in King of the Monsters reflects the broader unequal representation of women in popular media.