Review by Molly McKew

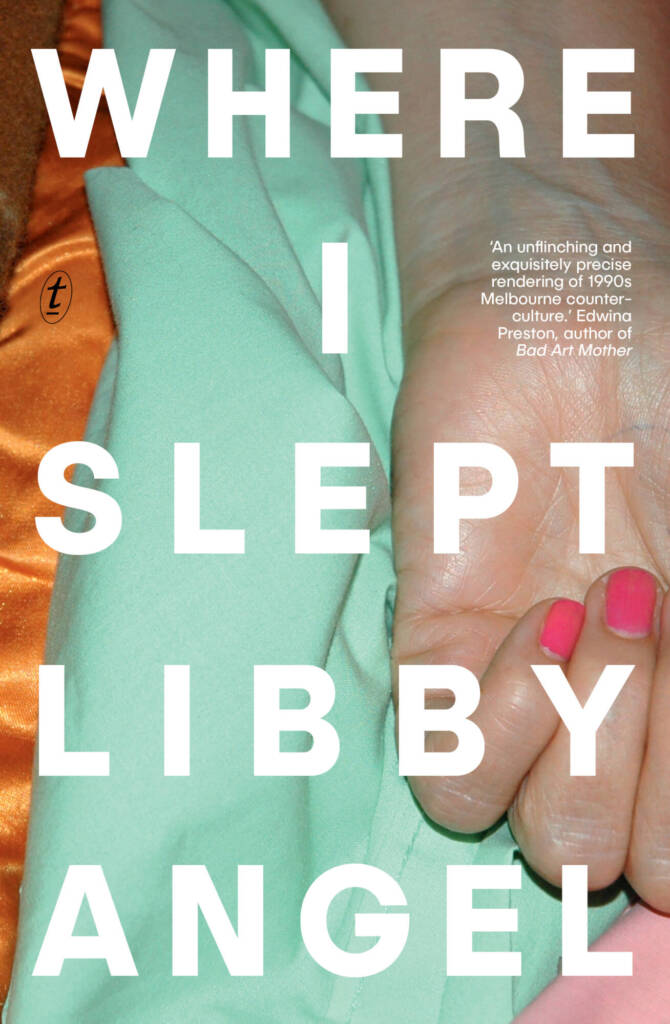

Libby Angel’s Where I Slept paints a rich and immersive picture of the artistic bohemia of 1990s urban Melbourne. The short, observational chapters tell the story of a young woman ensconced in a journey of something that is not quite self-discovery — she is strong in her skin and knows who she is — but of finding a place in which to thrive.

Libby Angel’s Where I Slept paints a rich and immersive picture of the artistic bohemia of 1990s urban Melbourne. The short, observational chapters tell the story of a young woman ensconced in a journey of something that is not quite self-discovery — she is strong in her skin and knows who she is — but of finding a place in which to thrive.

The novel, a work of auto-fiction based on Angel’s own experiences, begins with our narrator residing in a boarding house in a town in country Victoria she nicknames ‘Tidy Town’. But she is soon drawn to the city, where she sleeps on the couches of various friends before finding a room in a cheap terrace house she names “number 47”. The house isn’t communal as such, but its inhabitants become close after they trail after one another to various social events, performances, pubs, cafes, or shoplifting and breaking and entering expeditions.

The narrator, unselfconsciously and with no specific ambition, wishes to be an artist of some sort. After painting an octopus on the wall of number 47 she has an encounter with her landlord: “‘You’re not an artist’, she said, ‘you’re just a spoiled child’.” She doesn’t mind that she might suck. “I hope you weren’t paid for that,” says an acquaintance, after a gig. “Because that was really shit.”

Purchasing a cheap saxophone, she soon teaches herself how to play, joins a band and later starts busking in the city to earn money. She joins a dance group, learns yoga, and engages in sporadic performance art. But her main calling seems to be poetry. Using an Artline 90 pen, she scrawls vague and pithy sentences in public places when the mood strikes (most relevant; ‘where I slept’, drawn during a period of homelessness). In between artistic pursuits, the protagonist spends her days busking, drinking tea in Greek cafes and beer in backstreet pubs, engaging in fleeting sexual encounters, and occasionally indulging in longing for a musician nicknamed ‘Winterman’.

The book is coloured by a lack of rootedness, sentiment, future, or past. We know nothing of the protagonist’s family, nor anyone else’s. It is clear that she is middle-class in origin and taste (“we are the undeserving poor”, she says when visiting a food bank). One year, a squat she is living in hosts an orphan’s Christmas Day lunch. “Nobody talks about their families. What is there to say? Absent fathers, single mothers, drugs and a bottle of gin”, she writes. The household, and by extension many in the protagonist’s broader friendship community, are bound by trauma and their lifestyle as largely middle-class bohemian drop-outs. “Our tragedies are comfort. We are not ready to part with them”.

Despite a refreshing lack of moral posturing, or even direction, the narrator is clearly a proud feminist. When the husband of a character nicknamed “Blond Housewife” calls her looking for his wife, who he accuses the protagonist of “losing”, she spits down the phone: “women are not objects that can be lost”. (Blond Housewife has disappeared to the beach to have a psychotic breakdown).

Angel’s descriptions of squalor, drugs, drinking, stealing and dishonesty are neither romanticized nor judgemental. Allies, enemies, tragedies and victories come and go and Angel takes a morally aloof but humane pleasure in the unfolding of character and the drama of trajectory.

Where I Slept also provides a cultural history of the arts scene of Fitzroy in the early 90s, traversing pubs, cafes, arts and activist movements, as well as specific pockets of the suburb such as ‘Little Spain’, a landing spot for waves of Spanish and Latin American migrants. Leftie-Melbourne 90s nostalgia abounds, with soy milk, rice cakes, yoga, dreadlocks, and Freudian phrases like “penis envy” in play throughout its pages.

After the housemates are evicted from number 47, the protagonist has a short period of homelessness, and we are taken through an endless (and often disgusting) search for warmth, food, money, and places to sleep. There is a sense that her friends are worried as they admonish her for her stubbornness, and for the first time we are invited to reflect on, well, whether the protagonist is even ok? But this opportunity is swept away in the promise and excitement of her impending move to another, larger, international city. She has proven her strength and by the end of the novel we are all for it. The novel is, in the end, a sort of ode to exploration and personal growth. “This city is just a big town”, she writes, “and I want to go to a metropolis