Writing by Freya Robinson // illustration by Cat Willett

In 2012, Bic’s ‘For Her’ ballpoint pen was the subject of international mockery. News outlets pointed and laughed as it was torn to shreds by Amazon reviewers, and an Ellen skit making fun of it now has over seven million views. Generally, it was agreed this product stank like absolute dog breath. Surely it was obvious that the 21st century did not call for girly pens, she-aring aids, screwdrive-hers or any other universal need repackaged for delicate feminine sensibilities?

In 2012, Bic’s ‘For Her’ ballpoint pen was the subject of international mockery. News outlets pointed and laughed as it was torn to shreds by Amazon reviewers, and an Ellen skit making fun of it now has over seven million views. Generally, it was agreed this product stank like absolute dog breath. Surely it was obvious that the 21st century did not call for girly pens, she-aring aids, screwdrive-hers or any other universal need repackaged for delicate feminine sensibilities?

In 2024 however, when products are marketed as essentials for being ‘that girl’, ‘vanilla girl’, ‘clean girl’, ‘tomato girl’ and many other phrases that make me want to hit myself over the head with an aged block of parmesan, it feels like the Bic pen could thrive if only it rebranded as a biro for your ‘girl diary’.

This trend of ‘girlhood’, formed in the wake of Megan Thee Stallion’s ‘hot girl summer’, has eclipsed the ‘core’ suffix that defined trends and aesthetics until recently, and now categorises everything from walking to eating, working and parenting, by gender, in a way often claimed to be empowering.

It’s particularly interesting that so many identify with the ‘girl’ prefix, given that the term ‘girl boss’ was derided for being patronising by a similar-aged cohort only seven years ago. In fact it was only in seeing the same sector of people championing ‘girl dad’ merchandise that proudly sported Jenny Holzer’s viral ‘raise boys and girls the same way’ t-shirt in 2015 that made me realise how much our online spaces have changed.

Initially, to me, this pivot felt like being headbutted by a Shetland pony – not ideal, but mostly harmless. It makes sense that in today’s climate many feel more comfortable identifying as girls than women, given young adults are more likely to live with their parents, and less likely to have financial independence or their own children.

But this is not girls as in ‘Who Run The World?’ This is placing ‘hot girl’ before every action a woman does, while men do the same gender-free. This is people unironically wondering why they feel that Cottagecore (the romanticisation of homemaking) has a ‘feminine energy’, while ‘Dark Academia’ (the romanticisation of higher education) is inherently male. This is ‘the feminine urge’, ‘the divine feminine’ and ‘womb energy’ baiting people to whip out a copy of Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus. Suffice it to say, now when it comes to ‘girl’ trends, I feel I have the wherewithal of an elderly labrador.

The most renowned of these gender-defined memes is arguably ‘girl dinner’, usually referring to dainty portions of babyish snacks eaten as an evening meal. The case made in its favour is that eating snacks instead of meals frees women from the expectation of cooking. The problem with this theory, as Heather Parry explains in their Substack essay, is that women are not under pressure to cook full, nutritious meals for themselves – yes, for husbands and children, but the patriarchy has always been in favour of women themselves eating less.

While I personally would love to be able to eat a granola bar without it being remarked upon whether it’s in a girl way or a boy way, I think the defence of ‘girl dinner’ actually highlights a salient point, and perhaps reveals where this trend is coming from. The claim of freeing women from the work of cooking doesn’t stack up with the reality that the women participating in this trend are largely teens to thirty-somethings who were never at home cooking all day to begin with. What’s more likely is that the work they are tired of, and the reason they don’t have the energy to cook, is the poorly-paid gig economy we now live in (see also: lazy girl job).

While I completely understand wanting out of this late-capitalist fire-dungeon, the fact that these trends are gender-specific – and you rarely see an equally infantilising male counterpart – plays into stereotypes that women are soft, delicate and babyish, and uses that as a get out card, instead of rallying for better conditions (or even joyously floundering in an ungendered way, like the ‘adulting’ craze of 2017). In fact, this tactic is shockingly similar to the way the far-right use worker exploitation and decreasing work/life balance as reasons to become a tradwife.

‘Girl math’, which ties poor financial decisions to femininity in order to justify unaffordable purchases, highlights exactly this. Considering women could be denied a credit card for exactly this reason just 50 years ago, unless you’re wearing misogyny horse-blinkers – this is also the point where any dregs of feminism firmly sliver off into the distance. However, Tiktok’s latest maxim: ‘I’m literally just a girl’ (Gwen Stefani circa 1995 would like to have a word with you!) is perhaps the most egregious example. A direct plea to get out of responsibilities, it uses a fragile feminine stereotype as a shield, like an antebellum maiden fainting in the heat , or the ‘Karen’ weapon of choice: ‘white women tears’.

Obviously girl trends are less serious than that. I understand the calls for journalists to put away the latex gloves and stop dissecting things that are only meant lightheartedly. But I wonder what attitudes make these jokes relatable in the first place. Why do these universal experiences seem feminine?

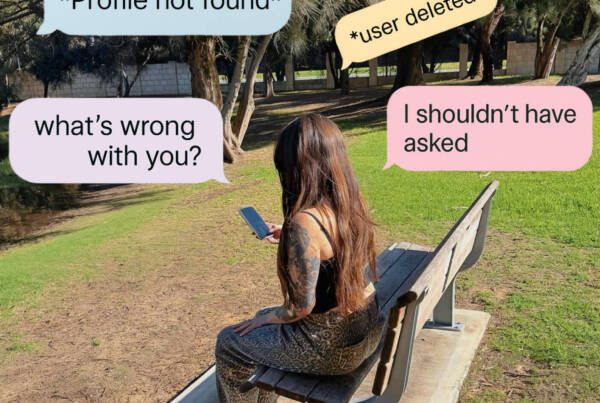

It’s also worth noting that, because these trends exist almost entirely through social-media, they are largely performative. Where previously you may have eaten a cracker without self consciousness, now it is documented online as ‘girl dinner’. Where you may have walked the streets of a Mediterranean city thinking only of the warm sun on your back, now you see the perfect lighting to show the world your role as #tomatogirl. To quote Margaret Atwood: ‘You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.’

I’m sure many will say they do these things for themselves, and – genuinely – I have no problem with adult women wearing bows or playing with dolls, or whatever else rocks your socks. But despite the suggestion that the girlhood trend is a reclamation of childhood taken too quickly, it doesn’t seem people are actually doing much other than buying.

It’s notable that there has been no resurgence of childhood games – no finger painting, glitter macaroni portraits, pooh sticks, hide and seek. No digging out of clunky Nintendo DSs or old pairs of jelly shoes. No stories relished and remembered, and none of the personal trinkets or DIY collage kits seen in the previous decade’s documentation of girlhood via Rookie Magazine.

Instead we cycle through package-deal yassified personality-of-the-months. ‘Mob wife’, ‘office siren’, ‘strawberry girl’ and the like are all flat archetypes of thin white women – not that dissimilar to the ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’ – that thrive through articles and Tiktok hauls identifying which products the consumer should buy to achieve this persona. Here women are treated as a commodity – one that can be picked up or dropped at the winds of capitalism.

At this point we have to ask why we are using objects to create a personality around in the first place. In all likelihood, it is the same reason we see shaving companies pertinently advertising themselves as feminist, and why Galaxy tells us that buying their chocolate bar will help build a well for a woman in Guinea Bissau. As Carlee Gomes highlights in their essay for Lo Specchio Scuro: “We’ve been stripped and socialised out of any real political energy and agency. Our ability to consume is the only thing remaining that’s “ours” in late capitalism […]. When the act of consuming is all you have left and indeed the only thing society tells you is valuable and meaningful, the act must necessarily be a moral one.”.

So what has changed since Bic’s ‘For Her’ pen? Well, a lot. Between 2012 and 2018 we saw the rise of the internationally recognised feminist campaigns Free the Nipple, the Everyday Sexism Project, and Time’s Up (the organisation connected to #MeToo), all of which have now ceased operation, as well as the viral 2014 mattress performance, Ni Una Menos and the Green Wave which captured hearts and minds globally. Despite the landmark overturning of Roe v. Wade, as yet, no large scale feminist movement has appeared to take their place.

The choppy waters of the culture war have left us in an exhausting, overwhelming, and uncertain time, with many are apathetic to political change. After so long selling glittery pencil cases with the message that you can do anything, maybe this is what happens when women feel they can’t. It’s clear that feminism is crying out for a fifth wave, but to many ignorance is bliss, and when you are only a girl you are too young to know.