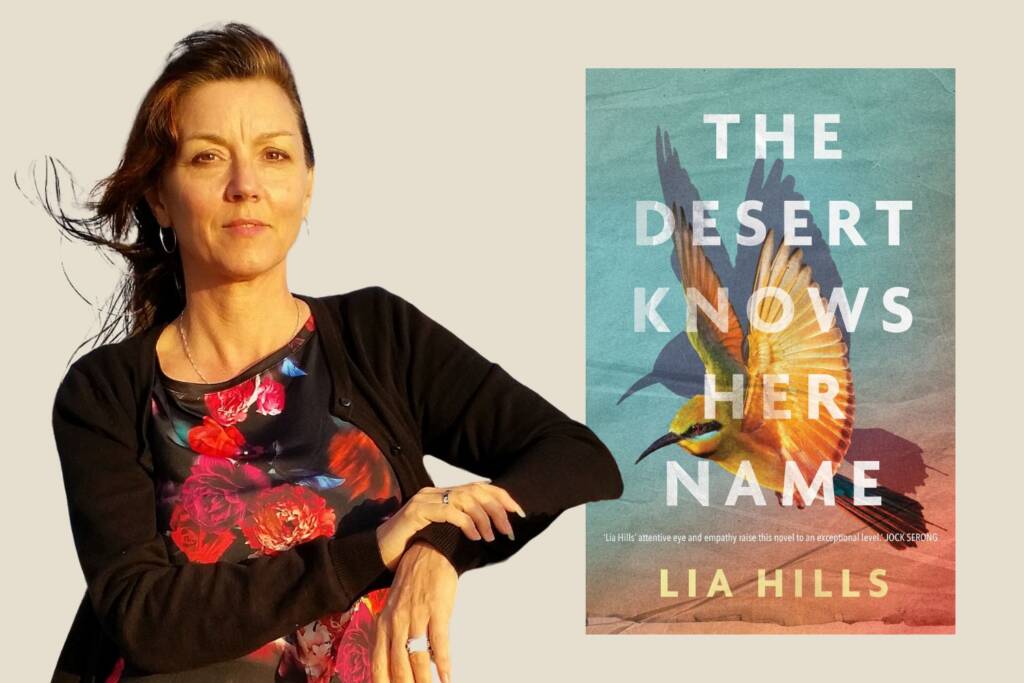

Writing by Lia Hills

Heat shimmers in layers above the Western Highway, so that it’s more like entering a body of water than a road. I’m on my way to the Wimmera in north-west Victoria. It’s early autumn 2019. For the last six months, the loose idea for a story has been rattling around in my head, about a girl who walks barefoot out of the desert – a girl who can’t or won’t speak. I’m in search of the right setting: a desert, a river, a small town (over the years to come, I’ll spend hours circumnavigating the south-eastern perimeter of Little Desert National Park, certain that something about the lie of the land or a gathering of mallee trees will tell my I’ve arrived). I’m also after a feeling that won’t yet articulate itself, though I know it will. In the process of attaching a story to a place, a kind of resonance emerges that always stays with me. A melodic mapping. Or a love song. One that adapts to all the flaws and wants of the storyteller.

Heat shimmers in layers above the Western Highway, so that it’s more like entering a body of water than a road. I’m on my way to the Wimmera in north-west Victoria. It’s early autumn 2019. For the last six months, the loose idea for a story has been rattling around in my head, about a girl who walks barefoot out of the desert – a girl who can’t or won’t speak. I’m in search of the right setting: a desert, a river, a small town (over the years to come, I’ll spend hours circumnavigating the south-eastern perimeter of Little Desert National Park, certain that something about the lie of the land or a gathering of mallee trees will tell my I’ve arrived). I’m also after a feeling that won’t yet articulate itself, though I know it will. In the process of attaching a story to a place, a kind of resonance emerges that always stays with me. A melodic mapping. Or a love song. One that adapts to all the flaws and wants of the storyteller.

On the edge of the highway, an old Holden has an abandoned car sticker on its windscreen. As I drive past it, all its tyres punctured, I’m reminded that we don’t always get where we’re hoping to. A good part of my twenties, I spent on the road. I wanted to understand and write about the world and was convinced that I could only do that by seeing it firsthand. I’d grown up in Aotearoa – witnessed the consequences of colonisation, but also Māori linguistic and cultural revival – before my family moved to Tasmania, a land in denial. I wanted to know if it was possible to leave behind the narrative I was raised on and write my way to something new. I also recognised the creative writing classroom wasn’t for me. I’m not good between closed walls. Much better to listen to others’ stories, in the place they call home; learn how those operate in their world, as framework, transmitters of knowledge, social glue; a form of resistance against power structures that have no interest in nuance and seek to erase.

Later, when I moved back to raise a family, I sought ways to replicate the fluidity and communion my travelling life had offered. I adopted the liminal space of my back veranda as a study – not out, not in. And this: taking a story on the road.

To people who might inform it, with their fears and desires.

To places torn apart and remade, over and over, on contested ground.

*

I drive through Stawell and come out the other side. Expand into the hum of tyre on bitumen and the way everything becomes metaphor on the road. But my ‘desert girl’ story is in search of the real. At a pit stop, I could meet a protagonist. Smoke rising from field stubble shapes into a theme. A song on the radio suggests the cadence of a narrator. The road markings, ellipses.

I’ve already contacted some people to introduce me to the Wimmera.

A Wergaia Elder, who’ll take me on Country, show me his boyhood sleeping place by a billabong and tell me stories that will caution my heart.

An epic poet who’s been teaching a philosophy class in a small town for almost a decade, a month’s-worth of lessons on the pre-Socratics exploded into the whole Western canon.

A local performance artist and member of the climbing community, with a penchant for leviathans and salt lakes.

All the meetings will go better than I’d hoped and, by the end of the month, I’ll have lined up an old farmhouse on the edge of Wyperfeld National Park, to work on the first draft of the novel that will become The Desert Knows Her Name. The farmer who’ll lend me the house, I’ll meet while trying to track down an elusive portrait by the street artist Rone, who painted one of the silos on the popular tourist trail but, according to rumour, also did a portrait on a ruin, its location a secret. So much feels fortuitous. Some makes it into the book. The rainbow bee-eater that greets me each morning of the two weeks I work on the first draft will eventually grace the cover – tearing its way out of the human narrative, as I once tried, and failed, to do.

During that first trip, the divide between fiction and the so-called real world blurs again and again, and the places I spend time in begin their melodic mapping, a song that suggests other truths. On the return journey, I spend a night beside the Pink Lakes of Murray Sunset National Park. As the sky turns blood-red and the pink of the salt lake deepens, I sink my fingers into the damp crystals, feel their sting on a cut – the expanding and contraction – salt water a good conduit of electricity, but also of history that night. In the north-west, frontier violence was brutal and swift, and these histories will become core to the story. Falling asleep in the back of my car, the salt lake reflective beneath a full moon, I think about the girl alone in the desert – the one I’ll spend years writing – and wonder how and why she’s brought me here.

*

Beside me, as I write this piece, lies the journal I kept during that first 2019 trip. Flicking through it, I become that woman again, heading up the Western Highway, the Wimmera not yet populated with the bird and plant experts I’ll meet; members of the land council and local Aboriginal community who’ll help me through various drafts; regenerative farmers who’ll try to cure me of my grass-blindness; and all the sounds. The susurration of the Bulokes, the wind harps of the Wimmera. The screech of the Long-billed Corellas after who the fictional town will be named.

So much of my novel writing is done alone, but the instinct persists – to find the communities of the story, ones connected to its place.

To listen.

To walk alongside.

As I close the black cover of my journal, I can no longer imagine writing a novel any other way.

Lia Hill’s book The Desert Knows Her Name is out now through Affirm Press.