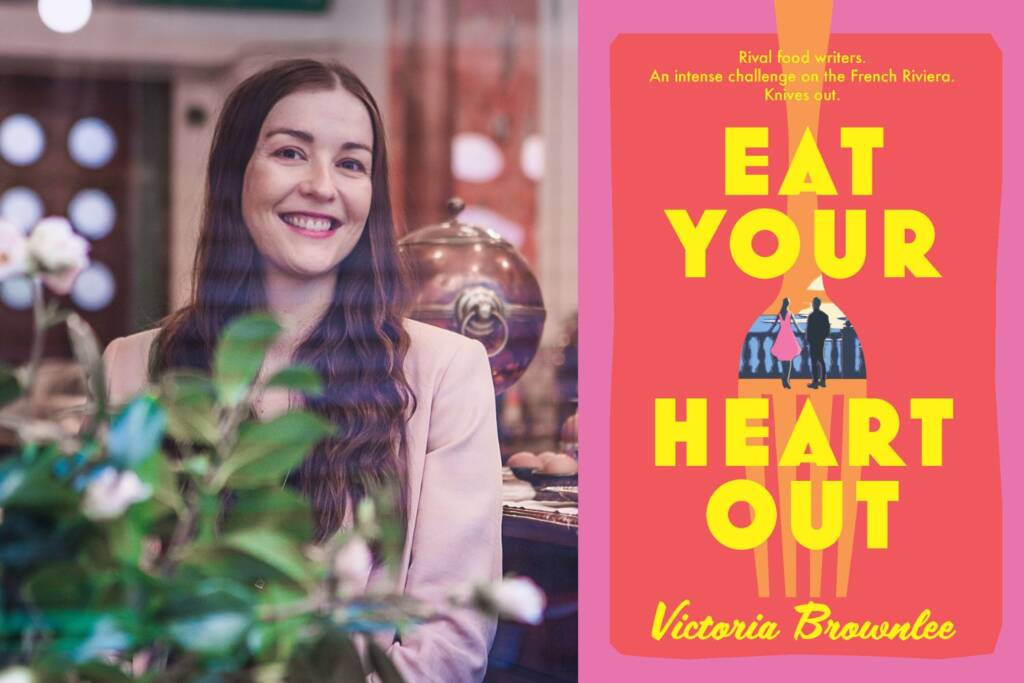

Words by Victoria Brownlee

The water isn’t running in our newly-installed bathroom tap. Jean, our neighbour and a plumber, swings by to take a look at 8pm while we’re having dinner. I’d spoken with him a few days earlier, and he’d said he’d be there when he got a free minute, so it wasn’t as though he was coming unannounced.

The water isn’t running in our newly-installed bathroom tap. Jean, our neighbour and a plumber, swings by to take a look at 8pm while we’re having dinner. I’d spoken with him a few days earlier, and he’d said he’d be there when he got a free minute, so it wasn’t as though he was coming unannounced.

Showing him the problem tap, he says to me in French, ‘Pas de problème!’. I leave him to it, going to get my glass of rosé. A few moments later he comes out asking if I have a cork. I give him a confused look. Impatiently, he sees the wine on the table, spots the cork, grabs it and returns to the bathroom. I raise my eyebrows at my husband and he shrugs. Minutes later, Jean re-emerges. ‘I fixed the toilet,’ he tells us. ‘But it was the tap,’ I splutter. ‘Oh, I fixed that, too’, he replies.

The plumber takes his leave and once he’s gone, I go check the bathroom. The tap is running perfectly. Success. And then I turn to the toilet and see the cork. It’s sitting atop the toilet attached to the string that pulls the flusher. I might have been upset, but the cork actually looked quite charming. The main thing I cared about was having running water from the tap. The broken, and now fixed, toilet was just collateral damage. I took solace in the fact that I would need the plumber again soon. That was the beauty of living in a 300-year-old house. There was always something breaking, bursting, crumbling or leaking.

But let me rewind. In 2019, my husband and I smugly packed up our 60 square-metre Parisian apartment, scooped up our sleep averse one-year old, and headed south. We were entering our tree-change era. We were going to embrace village life.

The 18th Century stone house, huge in comparison to what we’d had in Le Marais, was split over three levels, plus it had a small pool, a little garden (oh my, how I loved my wisteria vine, until it came time to trim it) and a workshop space. The heating ran on fuel (payment required by cheque) that had to be delivered by a tanker too big for our driveway, forcing all traffic on the village’s too-narrow main road to a halt. There was a wine cellar the size of our first studio apartment in Paris that my husband tended to more than the wisteria and there was an incredible view from the second-story terrace that overlooked rooftops and the Luberon mountain ranges.

There was a reason we’d felt smug. The house oozed charm and we blissfully entered our honeymoon period, exploring the postcard-perfect Provence hilltop villages, shopping the riverside antique markets of Isle-Sur-La-Sorgue for mid-century modern gems and over-priced antiques, and driving down to Marseille for a quick Bouillabaisse and a dip in the Mediterranean Sea. I set up a desk overlooking our courtyard and while I wrote, I would watch the birds darting between the wisteria and into the vines. The birds had babies. Life felt sweet.

But then, after we’d arranged our furniture and settled in, we began to make a modest list of things we wanted to do in the house. Mostly cosmetic changes as we were limited by our lack of renovation experience and by what we could do with a small child in tow. We’d paint over some of the feature walls, update the bathrooms, and maybe change a few things in the kitchen (spoiler: we’d replace it in its entirety). We weren’t in a rush and we planned to do things slowly and meticulously, enjoying the process and stopping often to refuel with food and wine.

And thankfully our plans started out as modest, because we soon came to realise that there was only one speed for renovations in Provence, and that was slow like an escargot! The biggest challenge wasn’t the work itself, but finding someone willing to do the work. I’d expected them to operate in a similar way to Australia – call, visit, quote, book-in, job done – however, in France, I seemed to be getting stuck on the first part of the equation. Phones went unanswered, messages ignored. Finally, somebody would turn up, but then they’d take one look at our narrow staircases never to return again. We puzzled over how to pay somebody to do work on the house. Did these people just not need the money?

And thankfully our plans started out as modest, because we soon came to realise that there was only one speed for renovations in Provence, and that was slow like an escargot! The biggest challenge wasn’t the work itself, but finding someone willing to do the work. I’d expected them to operate in a similar way to Australia – call, visit, quote, book-in, job done – however, in France, I seemed to be getting stuck on the first part of the equation. Phones went unanswered, messages ignored. Finally, somebody would turn up, but then they’d take one look at our narrow staircases never to return again. We puzzled over how to pay somebody to do work on the house. Did these people just not need the money?

So, we did what any first-time renovators would do, and tuned into YouTube, doing as much around the house as we could, rewarding ourselves with long lunches at our local bistro (where 12 euros would get you a dish of the day, a mini carafe of red/white/rosé and a coffee and dessert). Renovation refuel.

Lo and behold, one lunch, we end up next to the handyman who was meant to come and repair our window shutter. We begin chatting and he offers to come and take a look after he’s finished his espresso and his crème caramel. A-ha! In a moment of pure serendipity, we’d cracked the code.

From then on, if a pipe burst, we’d pop down to the local bistro and wait until the plumber polished off his coq au vin. When the electricity blew (perhaps in part because our fuse box looked like a school project), the electrician would swing by after a ‘quick’ steak-frites.

Once we synched our project timelines to the rhythms of the village’s lunch break, we started making progress. We managed to replace the kitchen, convert the workshop into a studio with a bathroom and a kitchenette, paint lots of walls, replaster other walls, rip up the decking in the courtyard and replace it with a tonne of small rocks (that was a ‘fun’ day). I became one of the most loyal members of the French version of Bunnings, subbing the requisite sausage for a croissant.

The hardest part? Knowing where to stop. The more work I did to the house, the more I wanted to do. I would happily drop off my kids (yes, by this point there were two) at school and spend the day painting, only stopping for a quick 90-minute lunch break to go and enjoy a three-course meal with a glass of wine at the local bistro, while getting some advice on a cheaper paint supplier.

But as the years slipped by, Australia called and we decided to move ‘home’. On our final moving day, my husband reminded me that under no circumstances was I to start touching up the chipped paint in the bathroom, but I couldn’t help myself. I wanted our incoming tenants to love and treasure the house like I did.

Two years on, and I still haven’t felt the urge to pick up a paintbrush. I guess rolling flat walls just isn’t as interesting as hand-painting rock walls, or maybe it’s just that hard yakka isn’t as enticing without the 12-euro, wine-fuelled lunch break.

What my time in Provence really taught me – more than how to DIY a renovation or bribe a plumber with rosé – was how to embrace imperfection. Even better, realising that the imperfections actively contribute to the charm. In Provence, if a roof tile comes loose, you pin it down with a big rock. A light stops working, wasn’t it always just decorative? If your toilet breaks, open a bottle of wine, drink it, and when you’re done, use the cork to fix the flusher.

Victoria Brownlee is the author of Eat Your Heart Out (Affirm Press), out now.