Review and artwork by Seth Hynes

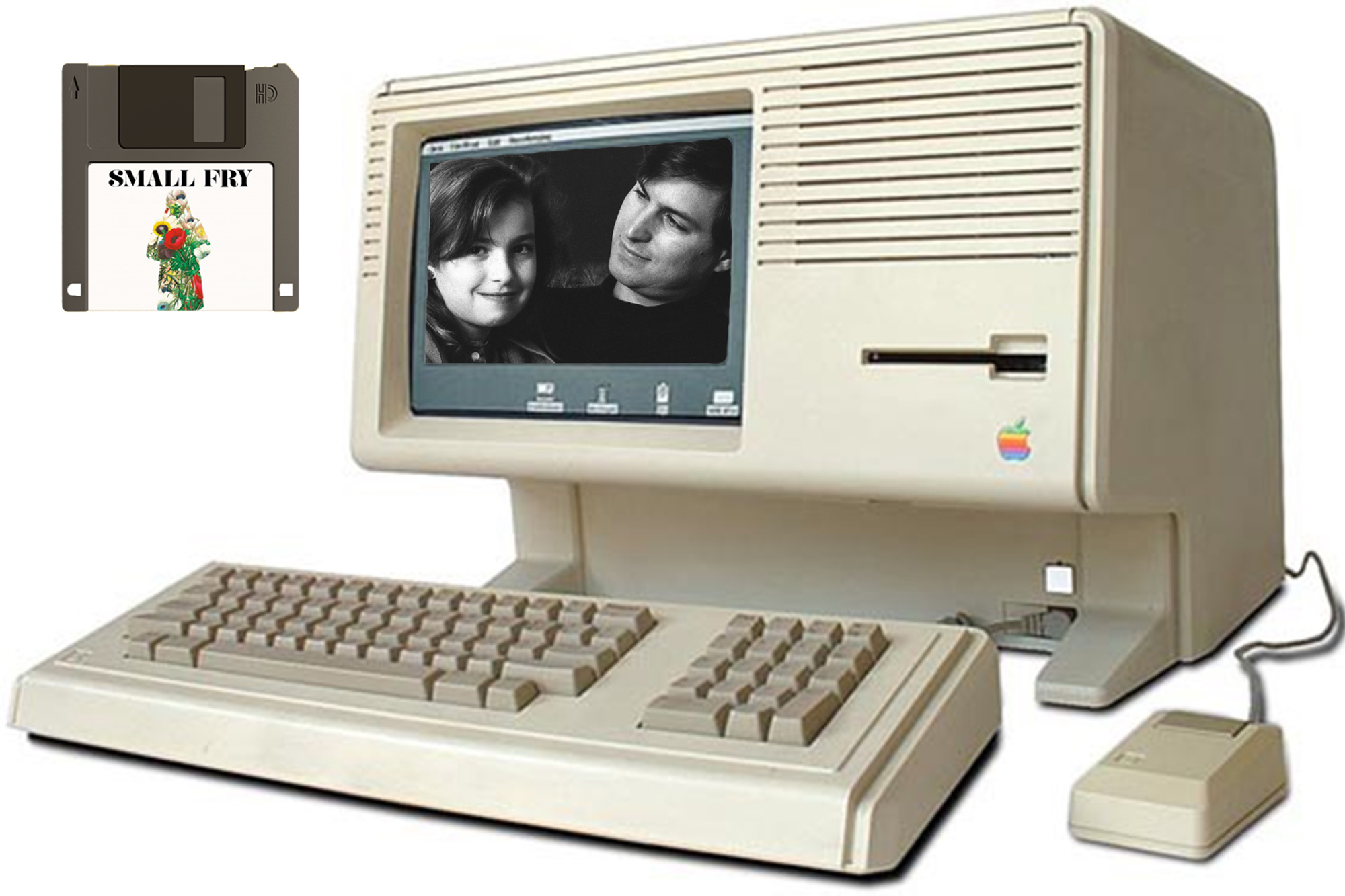

Published in September 2018, Small Fry is the memoir of Brooklyn writer Lisa Brennan-Jobs, the oldest daughter of Steve Jobs (1955-2011), the co-founder of Apple.

The memoir details Lisa’s difficult early life and her turbulent relationship with her emotionally (and often physically) distant father.

Lisa delivers beautiful, evocative prose and a remarkably lucid account of her past. She calmly ponders the motivations of her fragmented family, while acknowledging that she’s only scratched the surface of her inscrutable father, and Lisa herself (within the narrative) comes across as a smart, melancholic young woman forced to mature too quickly around her neglectful father and her depressed, volatile mother (artist Chrisann Brennan).

During Lisa’s childhood, Steve dispenses a drip-feed of emotional and financial support into her life. In the middle of the book, it’s gratifying to follow Lisa in her early teens as she grows from a slightly superficial slacker, fixated on make-up and collecting coats to compensate for the poverty she endured while her mother raised her, to an ambitious, dedicated student with a passion for literature and writing. Lisa’s perception of Steve also evolves: as a young child, she viewed him as a mysterious, strange figure of god-like charisma, but as she grew older, she came to both love and fear her father, and resent him for his regular coldness and detachment.

In some respects, Lisa’s experience of her father was both warmer and colder than the recent cinematic portrayals of their relationship.

Like in Jobs (2013) and Steve Jobs (2015), Steve denied paternity for a long time, but the films don’t show how, in private, Steve would have her stay over in his mansion sometimes or take her roller-skating or on drives in his Mercedes-Benz, experimenting with small fatherly gestures in a clinical way. There was no cathartic reconciliation on a rooftop, in which Steve finally admits that the Lisa computer was named after his daughter, like in the climax of Steve Jobs. In reality, Steve stiffly welcomed Lisa into his family during her early teens, but he remained demanding and distant, and Lisa describes her time living with her father, step-mother and siblings as extremely lonely. Steve only fully apologised for his neglect a few weeks before dying of cancer in 2011. The films also omit the fact that Kōbun (1930-2002), a Zen priest who Steve and Chrisann befriended, had convinced Steve not to support Lisa, shortly before she was born in 1978.

With sensitivity and precision, Lisa highlights the stark contrasts in her father.

Steve was a multi-millionaire, but led a frugal lifestyle (to the extent that his mansion never had a couch or fully-working heat, which were both emblematic to Lisa of her father’s general coldness). Steve would speak with enthusiasm and directness about design and industry, but was reserved and awkward in social situations, prone to absurd jokes or startlingly callous criticisms of others. Steve treated intimacy as either sloppy performative displays with his girlfriend Tina and (later) his wife Laurene, or as an impersonal checklist of Lisa being present in the home, doing her chores and babysitting her little brother Reed. Steve undeniably had many relaxed, genuine, warm moments with his daughter, and his sex talks proved very respectful and helpful for her, but he refused to say good-night to her – save for one time, after Laurene apparently pressured him into it.

It’s bad enough that Steve excluded Lisa from family pictures – save for, again, the rare case of Laurene intervening – but Steve never willingly saying good-night to his daughter, and even declining her requests, was to me, probably the most heartbreaking detail in the memoir.

On a side-note, I’ve sometimes wondered if Steve Jobs was autistic, and Small Fry reawakened my speculations. Autism manifests uniquely in all those who have it: I have Asperger’s syndrome, and I still have obsessive tendencies, write a lot of lists, fear embarrassment and teasing makes me uncomfortable, but I am proficient in small-talk, I have a small but rich social life, and I’m a writer, which seems to be a relatively uncommon profession among autistics. Steve’s earnest awkwardness, exceedingly particular nature and limited interest in others’ feelings – the last two converging in a degrading rant about a carrot salad dinner order at a Hawaiian resort – seem like strong signs of autism to me.

I saw small elements of myself in Lisa while reading Small Fry. We were both nerdy, lonely kids. We’re both writers. We both moved school several times, and in primary school, I remember not performing as well as I could have. I also have a segment of my family (my paternal grandparents and cousins) who I rarely see and show little evidence of caring about me.

The underpinning morale of Small Fry is about the impact of compromise, and how too much or too little can hurt people.

For so long, Steve refused to compromise on his bohemian, independent lifestyle to help raise Lisa, beyond child support payments and tiny gestures, but when he opened up a little and brought Lisa into his family, he still barely compromised for her comfort and wellbeing, but expected far too much compromise from her.

Steve never comes across as nurturing in Small Fry, and rarely gave Lisa his upfront compassion or time, but he demanded that she be ‘a part of this family’, to the point of stifling her social and academic lives. When the Jobs family were invited to a wedding at Napa, Steve and Laurene thrust babysitting duties on Lisa, as it never occurred to them that she wanted to join them at the wedding. A major sub-plot in the last third of the book concerns Steve pressuring his daughter to transfer schools so that she could be closer to home, thus forcing her to give up the class president role she had just won in a school she really enjoyed. Steve shows disinterest and even disdain for Lisa’s extracurricular activities and her goal of studying at Harvard.

Steve wanted Lisa ‘to be around, but in another room, in his orbit, not too close.’ While he cared about Lisa and was afraid to lose her, Steve would rarely compromise on his nebulous self-image of “father” to allow Lisa independence.

Steve expecting Lisa to be present more and more in the family home, despite himself having been absent for much of her childhood, is staggeringly ironic, and strangely un-self-aware for a man with such meticulous instincts, and Small Fry powerfully illustrates how excessive compromise, in either extreme or direction, is harmful in relationships.

Small Fry made me further examine my own indirect connection with Steve Jobs through the products he oversaw.

I’m a Mac fan and collector, but more of a nostalgic Mac fan. I own several vintage Macs, including a 2008 Mac Pro that I adore, and I’m fond of Apple from around the turn of the millennium, when they had the best balance of design, performance and power.

Steve Jobs wasn’t a bad person, but I found myself distrusting and disliking him from the insights in this book. We’ve all found ourselves grappling with morally problematic creators behind the media or products we enjoy. The awareness of Jobs’s aggression and neglect inevitably colours my Mac fandom; I’ve never felt guilty for my love of old Macs, but certainly reserved, and more so now, given the severely flawed and even cruel father arguably behind them.

Small Fry is an elegantly-written, poignant and deeply compelling memoir about unbalanced compromise and a lonely girl struggling to connect with a legendary, estranged father.

Good night, Lisa.