Writing by Miranda Michalowski

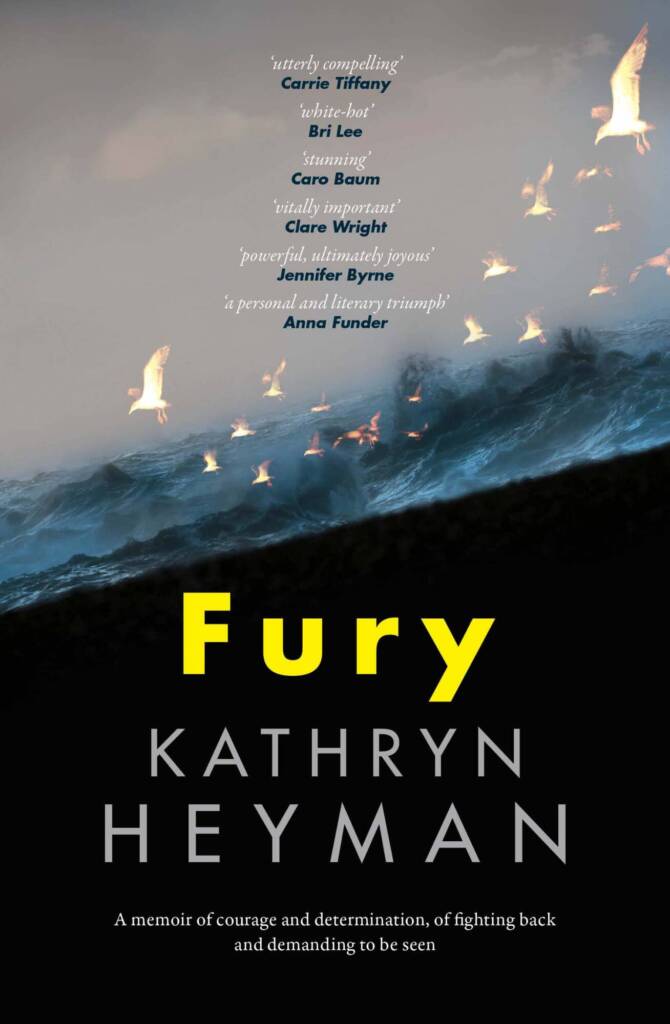

I have known the author Kathryn Heyman since I was a child. Her new memoir ‘Fury’, about her time spent working on a trawler on the Timor Sea, showed me a side to this woman I have never seen before.

I have known the author Kathryn Heyman since I was a child. Her new memoir ‘Fury’, about her time spent working on a trawler on the Timor Sea, showed me a side to this woman I have never seen before.

It’s a chilly Saturday afternoon in a Redfern Cafe and Fleetwood Mac is playing over the speakers. Across the table from me sits a woman I have known for years as a maternal presence, the mother of my childhood best friend. The blonde author smiles at me through her perfectly straight teeth and orders olives for the table. She places the recording phone precariously upon a stack of ginger beer cans.

Kathryn Heyman is a woman I have known for years as a writer, a mother and a highly educated woman. But there was a time when she went by another name; Kacey and led a life that was far from privileged. At age 20, after a traumatic sexual assault trial, Heyman ran away from her life, boarding a fishing trawler, ‘The Ocean Thief’ and travelling the turbulent Timor Sea. In her recently published memoir ‘Fury’, she tells the story of that girl.

As the author of six fiction novels, and the director of the Australian Writers Mentoring Program, Heyman is an established figure in the national literary scene, and the theme of male violence is a powerful undercurrent in her novels. ‘Fury’ is an adventure memoir, exploring what it means to grow up in a society that refuses to “see heroism in the shape of a girl”.

The memoir begins with the writer’s alleged sexual assault at the hands of a taxi driver. She writes, “My memories now, like the memories of early childhood, are without words, are purely bodily memories, a series of sensations in the dim dark. Heat. Light. Swerve. Sick. The formation of a single word: no.” She describes being painted as a “bad victim”, her clothing choice and drunkenness on the night of the alleged assault having been used to discredit her as a witness. The taxi driver was not convicted.

However, while the memoir begins here, Heyman’s story is a far larger one. ‘Fury’ is filled with vignettes detailing harassment from boys and men; experiences that trace back to the writer’s childhood. These stories are uncomfortable to read, and that is the point. “I knew that I was rigid about a kind of feeling that young women, to varying degrees, but most young women, by the time they get to adulthood have had some bombardment of unwelcome sexual advances,” she says.

Kathryn’s 22-year-old daughter, Seren, tells me that women of her generation share the same experiences. “When I was growing up as a teenager, my mum was

quite protective of me. She would always say, ‘It’s not because I’m worried about what you

will do. It’s because I’m worried about what other people will do, what men will do. Might

do,’” Seren says.

Heyman tells me that the memoir is more about what happens after fury, what happens after

she steps off that boat. However, she jokes that the title After Fury doesn’t have quite the same ring to it. Fury she says, is about the capacity for people to be transformed. “I’d read thousands and thousands and thousands of books… I think one thing that gives you, is it builds into your fabric an understanding of narrative possibilities… The narrative can be changed, it can be transformed,” she says.

Heyman and her daughter both echo that the naming of traumatic experiences is essential in

enabling a conversation to be had. “I think that articulation is absolutely crucial in being able

to address the problem, right? Because if you can’t even speak about it, it shapes the way you

think about it, the way you behave around it,” her daughter says.

As we sit together in the Redfern café, Heyman tells me about one of her favourite poems, To

The Woman Crying Uncontrollably In The Stall Next Door by Kim Addonizio. The poem is

about a woman speaking to a stranger crying in the bathroom stall next to her. The poet speaks of shared female experiences and how they create an invisible bond between women, with the final line “listen I love you joy is coming”. Heyman’s face lights up as she recites this line.

Sitting here now, opposite this woman I have known since childhood, I am 20 years old. The

same age she was when she boarded that fishing trawler and stepped out into the surging unknown. Into a world of shrieking dolphins and thunderstorms, of reckoning and rebirth.

Heyman writes “Mouth closed, face burning. Bile in the stomach. This is what it’s like to be

a girl, to be this girl.” I am sure that many women have felt like this girl throughout their lives.

I did not suffer the same hardships that Kathryn Heyman suffered in adolescence. I have been

born under the protective shelter of privilege. And yet, I still know the feeling of a man leering at my legs in fishnets from behind me on a crowded bus. I know the feeling of tight-throated fear that accompanies walking home alone at night-time. I know the feeling of being

groped while drunk on a trampoline and being told by the perpetrator’s friend that “he’s just a

weird guy”. I tell these stories because they are not unique. In Fury, Heyman articulates the

experiences that feel isolating to women but remain common to us all.

Her furious poetic voice speaks of the power that comes with naming trauma: “I don’t have a

sword, I don’t have a knife. I just have words.” It was through harnessing these words to reclaim her story that the writer was transformed. And just like the poet writing To The Woman Crying Uncontrollably In The Stall Next Door, Heyman’s voice reminds women that

they are not alone. That joy is coming.

1800 RESPECT – 1800 737 732

Lifeline – 13 11 14