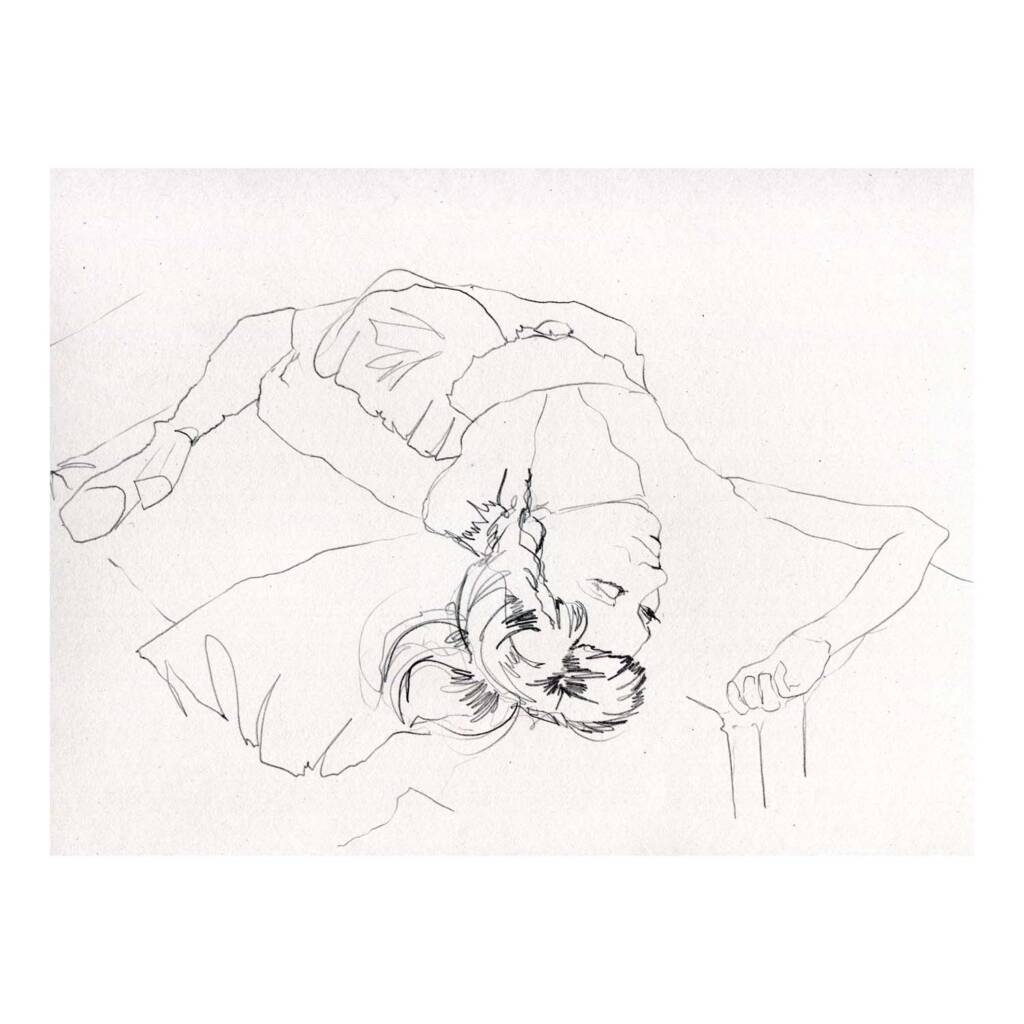

Writing by Juliette Salom // illustration by Isher Dhiman

There’s a ghost that lives in the bedroom next to mine. I only see her at night, when she creeks the floorboards of the house, mumbling like a drunk. She’s not scary, quite the opposite really. She wears striped pyjama pants and an old t-shirt with holes where the moths find it tastiest. In fact, she looks an awful lot like my sister.

There’s a ghost that lives in the bedroom next to mine. I only see her at night, when she creeks the floorboards of the house, mumbling like a drunk. She’s not scary, quite the opposite really. She wears striped pyjama pants and an old t-shirt with holes where the moths find it tastiest. In fact, she looks an awful lot like my sister.

Sleep has always come easily to me, I’m an envy fit for insomniacs, so I very well may have spent the first fourteen years of my life unknowingly living next door to a ghost. Fourteen often seems the age that the monsters under the bed start to become a little less scary than the ones in real life. Fourteen was the age I was when my sister started to become a monster. Isosceles teeth and an unpredictable temper tucked away in the small frame of a sixteen-year-old girl.

My parents called it adolescence, but there I was, only two years behind her in my own teenage-hood, yet still capable of being a human being. I guess it was just easier for my sister’s diagnosis to fall under that of the inevitable teenage angst, a monster that is promised to be cured with time.

We live in an old house, a Victorian skeleton that was built with a hallway and high ceilings on the ground level. But my sister and I sleep upstairs, in two adjourning rooms on the level of the house that is our own. Both of our beds are pushed against the same thin wall, one on either side. When we were really young, we used to talk through the wall, whispering and giggling until one of us eventually surrendered to sleep. It was almost like we were sleeping next to one another in the same bed; it was a comfort for us as little girls to know that we were not fighting the monsters under our beds alone. We don’t talk much through the wall anymore, not unless it’s yelling at one another to turn the goddam music down. Most of our other talking isn’t unsimilar to this volume; we’ve amassed a habit of escalation as soon we open our mouths.

My sister has always been a sleep talker, a whispering choir without any lucidity. The wall we share is thin enough to hear even if one on the other side is talking only softly, but thick enough to not know what it is they’re saying. It was for this reason that her night-time murmurs never bothered me, they were only just ambience set to the tone of the darkness. But then one night I awoke not to the whispers of my sister, but to the mumblings of a ghost.

That night I realised that the wall between my sister and I was not only sound proofed by the plaster and planks that held it together, but by the TV downstairs and the birds outside and the cars going too fast down our street that littered the daytime sound waves. That night though, there was no TV, nor birds outside, nor cars on the street. That night there was only the ghost.

She never got out of her room that night, the ghost did not manage to open the door. My body had stiffened-still under the weight of my doona as I listened, not from fear or fright, but with sheer curiosity in wanting to hear the movements of the ghost next door. Eventually it gave up trying to get out. I listened as it mumbled its way back to my sister’s bed, the mumbles slowly morphing back to the soft snores of a sixteen-year-old girl.

Night-time began to be disrupted of any sort of healthy routine. I started waking up constantly, my dreams comparingly boring to the goings on of the ghost next door. Prior to my teenage-hood, sleep had been a reprieve. Now it was a spectacle.

As this nightly routine began to cement, I tried my best not to think about the new friendship I had found with this thing that looked so much like my sister. I tried not to think about how I preferred to share the company of a ghost, over a girl whom I share blood.

I never talked to my sister about the ghost. It was easier that way. It was easier not to talk to my sister at all. By now, I was sixteen, trying my best to resist monstrous tendencies of my own. I had grown fond of the ghost; she was a friend in the house. Perhaps she is the reason I never become a monster.

Sometimes if she couldn’t open the door for herself, I would lend a hand. Her eyes were always open, but the ghost couldn’t see me. If she were to venture further from the room in which she came from, I would follow. Always from a distance and always in silence, I tried my best to never wake the ghost.

It took until I was seventeen, now accustomed to our nightly expeditions, to understand the language of the ghost. Her mumblings were just that, but they carried the inflections and syllables of the English language. I listened to her, a ghost of drunken ramblings, and I started to talk back.

Our conversations were soft, and almost exclusively one-sided, but I didn’t mind. I hadn’t talked so easily with someone under this roof for years, the gentle practice of conversing had long ago become extinct in this house. The words that the ghost and I shared were only ever few, but this notion of talking for the sake of talking, for the sake of listening and responding and keeping each other company, seemed to pump life into the corners of this house that had only ever seen dust. Sometimes we wouldn’t talk, sometimes the mere presence of each other’s company said more than our mumbles ever could.

But the intimacy of our relationship went physically no further, it extended only through talking. I would never touch her, never block her path or try to wake the ghost from her trance. The last thing I wanted was for her to disappear.

And still, I never spoke to my sister of the ghost. I suspect she still did not know of its presence, even after our three years of friendship. She never brought it up. But I suppose I never asked. I barely saw my sister by then, now that I was eighteen and in my final year of high school. I would stay at the library into the evening to study, arriving home to quickly eat and shower before heading straight to bed. Early bedtimes were my attempt to fit some sleep in before I would meet my friend in the night.

Sometimes I would forget to wake up, the witching hour passing as my body replenished its energy without any nightly disruption. I would come to in a quick frenzy, the sound of kookaburras and garbage trucks alerting me of the meeting I had missed. But the ghost had still been out in the night, wandering the house and mumbling to herself, the evidence in the door to my sister’s room that had been left ajar.

One night I woke to a mumbling that was harried and hassled unlike any I had heard from her before. Sounds of distress pierced my dreams like a slap back to consciousness. I looked up from my bed to see the ghost in the frame of my door, silhouetted in her pyjama pants and moth-munched t-shirt. She should have been scary to see, a fright in the least, but, as usual, her presence in that of mine was only calming. Tonight though, she was talking fast, her ramblings more incoherent than usual. And then she turned, disappearing into the darkness.

I quickly slipped out of bed; my socked feet padded a few steps behind her. I had never seen a ghost move so fast. I followed her down the stairs and watched her as she circled the dining room table. It looked as empty in the night as it felt at dinner time, an old wooden antique of knife marks and sauce stains. But she didn’t stop to look at the table. In fact, I don’t know if she even saw it. She paced its perimeter in a trance, before abandoning the dining room in a hurry.

I followed her into the hallway, the heart of the house, the high-ceilinged corridor that connected each artery to the next. But she didn’t stop there, she wasn’t slowing down. Her mumblings were no louder, but they were indeed faster, disorderly sounds of stuttering syllables eating at the air around us.

But still, I did not stop her, I did not intervene. I watched the ghost make the length of the hallway and approach the front door. Again, I followed, close enough behind. But what had up until this point been careful precaution of polite personal space between the ghost and I, had now become a space that was extended to a point of danger. I watched as she opened the front door. She wanted to leave, she wanted to escape. I couldn’t blame her; I had wanted the same.

In my memory, the ghost stood in the doorway of our house for what felt like an eternity. What is only just a snapshot of what I witnessed, exists in my mind’s eye as a slice of forever. Because in reality, the ghost stood in the doorway for only a slice of a second, before slipping into the night outside the invisible boundaries of our house.

I ran to the doorway; I watched the ghost as she moved from the house to the wet cement of the road beyond. I watched her look toward me with a question on her face, instead of looking to her left as a horn pierced the darkness. And I watched the silver car, the one that was going too fast for a suburban street like ours. I watched at it tried to brake, as it finally saw what I saw, as it was too late. I watched the ghost, the ghost who had brough me life to this house, have her own be taken away.