Writing by Varsha Yajman // photograph by Claudia Soraya

From what I have lived as an Indian-Australian tutoring is almost a regimented activity.

Like in many South Asian families, I started tutoring early on in primary school. It was stressful but enjoyable, not asked for, but given with an encouraging nod. It’s the reason I can still multiply today despite ditching all maths the second I left high school.

I think academic support is taken for granted in many South Asian families and it’s almost expected as the norm to have one or more extra curricular tutoring sessions.

I recognise the huge amount of privilege I have in being raised by a family who fully supported and encouraged me academically. However, beyond just their wanting me to see a tutor, I myself wanted to see a tutor because I saw kids who looked like me in those classes. I saw the stereotypes in movies of the “brainiac Asian kid” and as much as I despise these stereotypes, I felt somewhat represented.

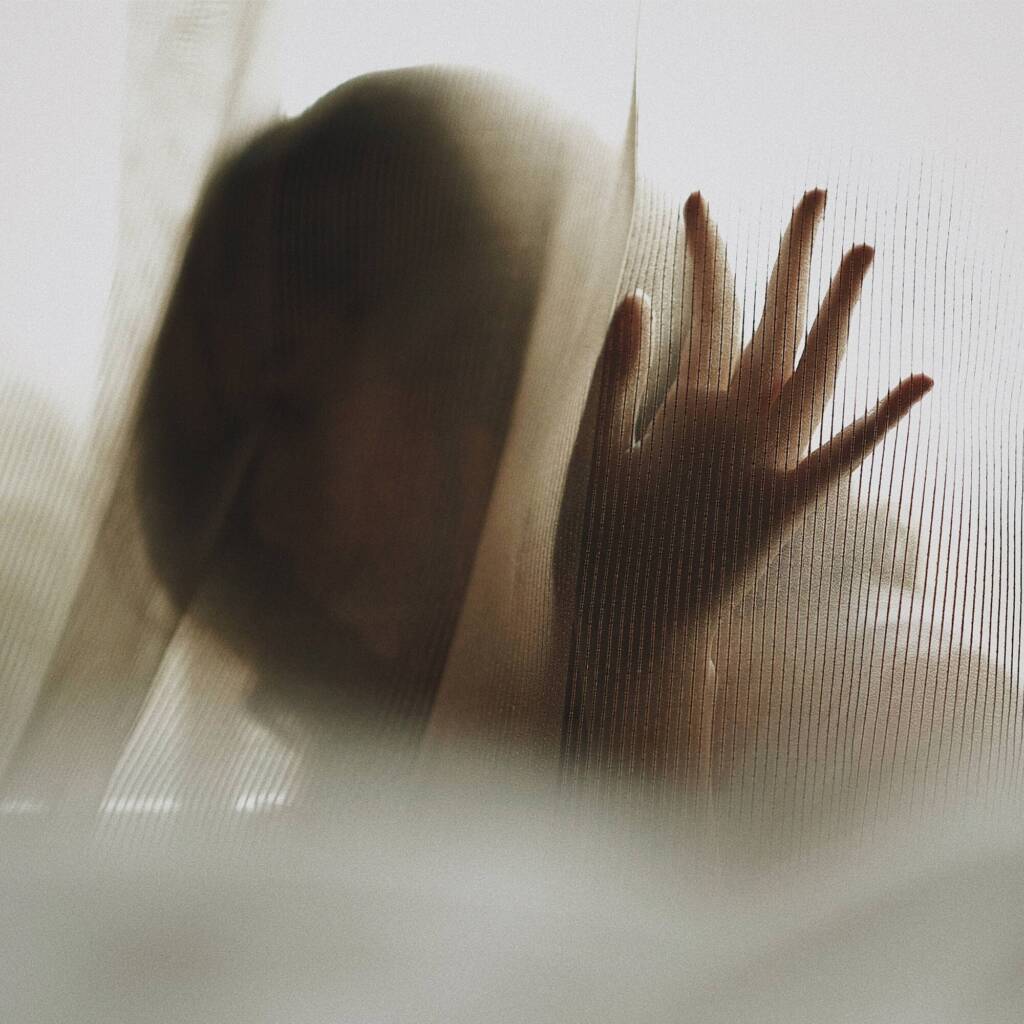

However, when I started to feel like I wasn’t coping mentally, seeking mental health support was a completely different story.

It’s only recently in shows like Never Have I Ever, that we see South Asian women being given the opportunity to seek mental health support, to talk about grief and eating disorders and how to deal with emotions that can feel all-consuming.

For most South Asians I know, there is a feeling of guilt surrounding the seeking of mental health help. There is this strange sensation in knowing how much more privileged you are than many back home and that makes you feel like you should be nothing but grateful and happy all the time. You hear about the “success stories” back home – those who “made it” without most of the things you had, and the guilt sets in.

It took 2 years of struggling with what I know now to be an eating disorder and anxiety to see a psychologist. The only reason I even began to see a psychologist was that concentrating felt difficult and it was my final year of high school – so it was still related to my academics. I think I almost saw my psychologist sessions as another form of tutoring. At risk, was my final year of high school and according to so many, my entire future. If I could concentrate better then I would get better grades. Of course, I now realise that seeing a psychologist wasn’t to make sure I got into my dream university but to simply feel mentally well.

Having the conversation with my family about seeing a psychologist was tricky. It’s not common in many migrant families to seek mental health support. Rather than seeing this support as a way to build up strength, as a way to cope with struggles, it can sometimes be seen as a point of weakness.

As a first-generation South Asian, I am aware that my family has had their struggles. They are immigrants, having to adapt to a whole new country, culture and language. They had to leave loved ones behind, leave precious memories and come to a country where their accent is made fun of, where they are not promoted at work because of the colour of their skin. I am also aware that many back home in India are struggling to make ends meet and it can feel like my mental health concerns are so trivial and indulgent despite being so lucky.

Over time, however, I began to realise that I did not need to be that “success story” we are constantly reminded of. I could seek help and still be grateful for what I have and still achieve my goals.

I was lucky to have the support of my Mum. We had the tough conversation and finally saw eye to eye, recognising the different perspectives we had because of the different country and generation we grew up in.

For much of my life and I know for so many, seeking mental health support can feel out of bounds because of ethnicity and culture. The reality however, is that mental health support, just like needing a maths tutor, was not created for a demographic, it was created for support.

Needing a psychologist does not make you any less grateful or strong, the same way needing a maths tutor doesn’t make you any less smart.

If you or anyone you know is struggling, reach out for help.